The Nikon FE2 isn’t quite as well known as some of the other mid-range film SLRs Nikon has produced. It is quite similar to, but somewhat shaded by, the engineering miracle that is the FM3a with its hybrid shutter. The mechanical FM series also seems to better known than the electronic FEs. However, despite being occasionally overlooked, the FE2 is a fine film camera.

The FE and FM Series

As one of Nikon’s semi-professional SLRs, the FE2 shares the same rugged, metal internal chassis and general design principles as its siblings, the FM, FM2, FE, FA, and FM3A.

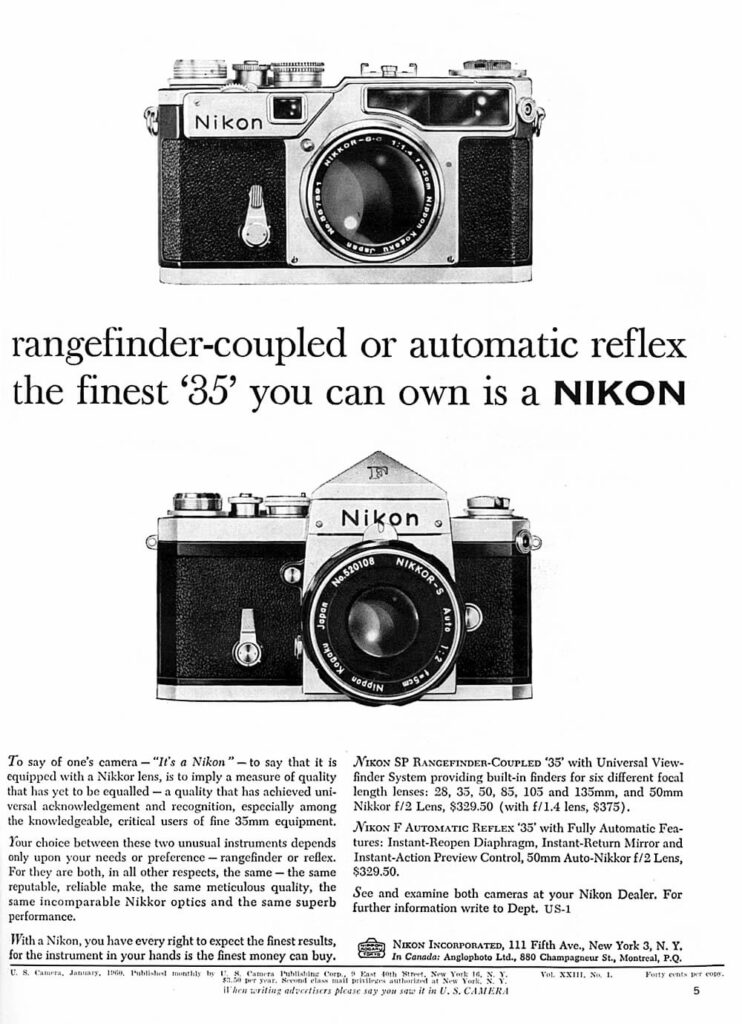

The FM and FE formed part of Nikon’s four product lines of F, FE, FM, and EM. These targeted different classes of users and were designed to change Nikon’s brand image from a manufacturer of high-end SLRs to an “all-round manufacturer”, accommodating a wide variety of consumers from beginners to professional photographers.

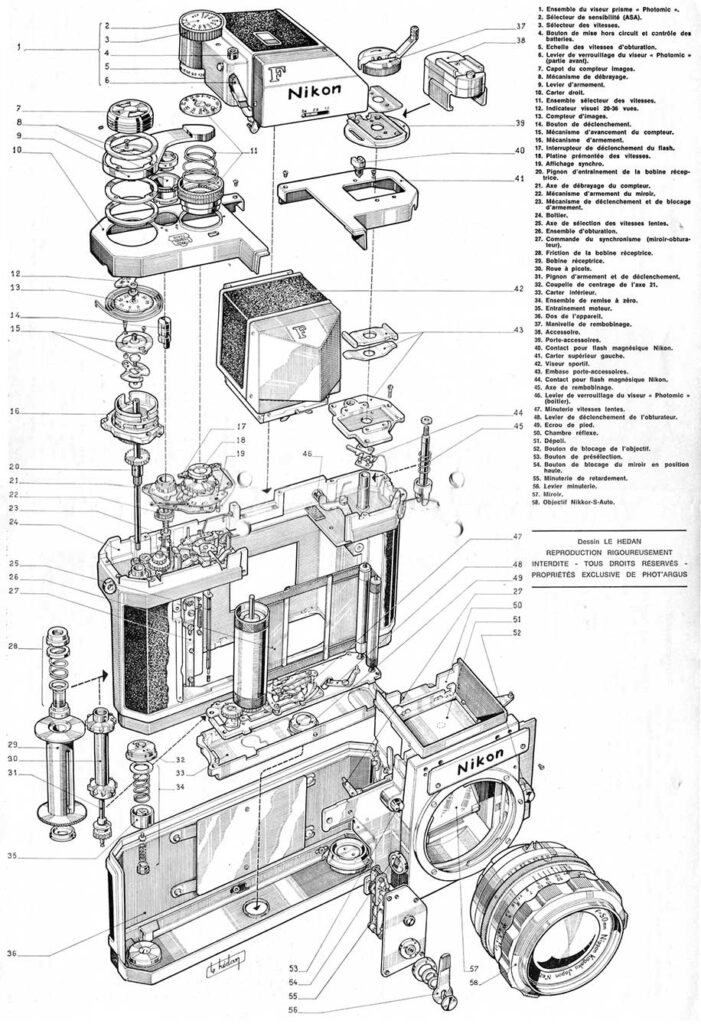

While they look quite similar, the Nikon FE and FM cameras are quite different internally. The Nikon FE and FE2 both have an electronic shutter with aperture-priority automation, and the light meter uses needle matching in the viewfinder. The FM is all-mechanical (except for the light meter) and uses a “centre-the-LED” system.

the table below provides an at-a-glance comparison of the FM and FE Series. Note that the later FE10 and FM10, manufactured by Cosina, sharing the same designation but based on a different chassis and designed for a different market, have been omitted. For brevity I’ve used the term ‘automation’ to refer to shutter automation, of which these cameras either offered none or aperture priority. For other automation options such as shutter priority, programmed auto etc. you need the Nikon FA.

| FM | FE | FM2 | FE-2 | FM-2n | FM3A | |

| Shutter | Mechanical | Electronic | Mechanical | Electronic | Mechanical | Both |

| Automation | None | Aperture | None | Aperture | None | Aperture |

| Max. Shutter Speed (Sec) | 1,000 | 4,000 | ||||

| Flash Sync (Sec) | 1/125 | 1/250 | ||||

| Lens Compatibility Since | 1958 | 1977 | ||||

| Introduced | 1977 | 1978 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 2001 |

| Discontinued | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1987 | 2001 | 2006 |

What Makes the FE2 So Good?

What struck me first about the FE2 is the how bright the viewfinder is. It is brighter than the FE and nearly as bright as the FM3A, with excellent close-to-100% coverage at 93%. The viewfinder is Nikon’s interchangeable Type K2 focusing screen with the useful split image rangefinder and etched circle that indicates the area of the centre-weighted meter.

The FE2’s feature I like most the intuitive needle-matching light meter, which is also used in the FE and FM3A (both of which are reviewed on this site). If you like a light meter, and I do, this analogue system is the most intuitive I have ever come across. It makes manual exposure so easy that I seldom use aperture automation.

The exposure lock works extremely well on the FE2, as the needle connected to the light meter locks once it is engaged. This isn’t the case with the FE – you just need to trust that it is engaged.

A fast maximum shutter speed is always a bonus for me, and the FE2’s operates at up to 1/4000-second shutter, which provides a lot of flexibility. This enables you to shoot with a wide aperture in bright conditions or use ISO 400 film on a bright day, which is advantageous if that roll is to be used in both bright and darker conditions.

The other features that make it a very capable everyday shooter for both beginners and advanced photographers are:

- Aperture priority automation

- 60/40 centre-weighted metering

- Exposure compensation (1/3 stop per click)

- Superb damping (so good mirror lock up was omitted)

- 1/250 sec flash (the world’s fastest sync speed SLR then in 1983)

- Choice of replacement viewfinders (replacement sets come with tweezers)

The FE2 Shooting Experience

Setting ISO Speed

The ISO film speed setting control is on the same ring as the exposure compensation control, on the right of the top plate, just like the Nikon FE. You depress the button to the right of the dial to set ISO and lift the ring to set the film speed. Lifting the ring feels both fiddly and slightly flimsy, compared to the smaller ring on the shutter speed button on the FM2n for example.

Loading and Unloading Film

Loading film is straightforward and much like other Nikon SLRs. Once you have slid the safety lock mounted under the rewind crank to disengage it, you can lift the film rewind knob. Nikon revised the location of the safety lock between the FE and FE2 and it the later model handles better as a result.

Once you have raised the rewind knob completely the back of the camera back pops open and you can load the film in the usual 35mm fashion – ensuring the perforations along the edges of the film mesh with the sprockets. When the film is engaged with the spool, press the camera back until it snaps into place. Unloading is similarly familiar: depress the button on the bottom of the camera and turn the re-winding crank in the direction of the arrow until you feel the resistance in the crank drop.

Power On

To turn the camera on, you pull the film advance lever open (to unlock the shutter release) and half push of the shutter release. The camera automatically shuts off to save power after a few seconds. The power source is two readily available button alkaline LR44s, or one more specialist lithium 1/3N battery. The FE2 can shoot at at 1/250s when the batteries are drained but without the light meter.

Through the Viewfinder

Looking through the viewfinder, the aperture you have selected is displayed in a small window to the top of the frame. This is the Nikon Aperture Direct Readout (ADR) system. To the left there is a shutter scale that displays both the selected shutter speed and a light meter readout via a pair of needles. The second longer, thinner black needle is connected to the light meter. In auto-mode this needle indicates which shutter speed will be used, whilst the thicker, shorter green needle is set it A.

In manual mode, the green needle is set by the shutter speed dial and needs to be matched to the light meter reading shown by the other needle. You can adjust either the aperture or shutter speed to obtain a match. It’s a great system, and in good lighting I much prefer it to the LED system of the FM2n (or the F3).

Lenses

I prefer prime lenses to zooms on manual focus cameras, and as I like to travel light I generally carry a wide 24mm and a standard 50mm. If I am travelling light I’ll might just take the excellent 28mm Voigtlander shown in the photo above or a 50mm. My 50mm of choice is the f1.8 AI-s pancake. All the lenses I use with the FE2 are AI-s.

FE2 versus the FE

The FE2’s predecessor, the Nikon FE, is similar to the Nikon FM introduced in 1977 but the internals are electronic. Unlike the FE2, neither camera features a model number on the front of the camera.

Advantages of FE2 over the Nikon FE

The most apparent advantage of the FE2 over the FE is that the faster shutter. The titanium focal plane shutter is two stops faster at 1/4000s vs 1/1000s for the FE, with the FE2’s flash sync at 1/250 vs 1/125. The backup mechanical shutter, which I don’t expect to need to use, is also more usable at 1/250s vs 1/90s.

There are other refinements: the viewfinder is brighter than the FEs, the light meter needle is locked stationary when the exposure lock is applied, and the exposure compensation is in 1/3 stop fine-tuning increments. (The FE’s scale is in 1/2 stops). The camera back lock also has been re-positioned, making it easier to operate.

Advantages of FE over the Nikon FE2

The Nikon FE has a surprisingly long list of small advantages over its successor. They seem quite minor to me, at least, but some photographers prefer the FE. As much as I have enjoyed shooting with the FE, on balance I prefer the brighter, faster FE2.

- Power Switch The FE’s power switch is very simple – just pull out the film wind handle. There’s an additional step on the FE2 – a half push of the shutter release. The camera automatically shuts off to save power. This seems to annoy some reviewers, but it doesn’t trouble me.

- Legibility in the Viewfinder The shutter scale speeds are more larger and easier to read than on the FE2, as there are two fewer speeds to accommodate. I only noticed this in a direct comparison between the two, though – it is not as if the FE2’s display is illegible.

- Battery Life This FE uses less battery power than the FE2 because its faster shutter needs stronger shutter springs and the batteries have to power the electromagnets to cope. All Nikons seem restrained in their battery usage, so this doesn’t trouble me either.

- Compatibility with Non-AI Lenses The FE can use Nikon lenses going back to 1959, while the FE2 can’t use non-AI lenses. I don’t have any non-AI lenses, most of mine are AI-s or AI.

- Battery Test Light The FE has a dedicated battery test light, which the FE2 lacks. This is definitely a nice feature to have but I don’t have it on most of the other cameras I use.

- Cost The FE is less expensive than the FE2.

Pre Frame 1 Metering

There is one difference between the FE and FE2 that you may see as an advantage either way, depending on your point of view. This is Pre Frame 1 Metering.

When you load a new film, the FE2’s light meter doesn’t operate until the counter on the film advance gets to frame 1. Before frame 1 (frames 00 and 0), the shutter always fires at its single manually operated shutter speed of M250 (1/250th of a second).

Nikon added this feature because if you have set the camera to auto and accidentally fire the shutter with the lens cap on or in a dim enough environment, the camera will set an extra long exposure – potentially tens of minutes long! This can be overridden by setting the shutter speed to a fast manual speed or the mechanical backup speed, M250.

The FE does not have this feature, so experienced film photographers can squeeze up to two more frames (frames 00 and 0) out of a roll of film, which they appreciate. These early loading frames are really designed to ensure by the time you get to frame 1, your camera is properly wound, and you don’t get partial frames, but they can be utilised for shooting in many cameras. They are numbered 00 and 0 to provide a reference number to reference them for prints, etc.

Discontinuation

The Nikon FE2 was officially discontinued in 1987. A quick glance at the Year-by-Year Camera Timeline on this site shows that the market was extremely dynamic at that time, with autofocus becoming established, along with the first glimpse of digital cameras and the emergence of the bridge camera.

- 1985 Minolta introduces the world’s first fully integrated autofocus SLR with the autofocus (AF) system built into the body – the Maxxum 7000 a.k.a. the Dynax 7000

- 1986 The disposable camera is popularised by Fujifilm with the 35mm QuickSnap

- The Canon T90 marks the pinnacle of Canon’s manual-focus 35mm SLRs

- The Canon RC-701 becomes the first still video camera marketed, offering 10 fps (frames per second) high-speed shutter-priority and multi-program automatic exposure

- 1987 Canon launches the EOS (Electro-Optical System), an entirely new system designed specifically to support autofocus lenses

- 1988 The Nikon F4 is introduced as the first professional Nikon to feature a practical autofocus system.

- The Fuji DS-1P, the first digital handheld camera, is introduced, though it does not sell

- The first of the Genesis series from Chinon helps to define the category of 35mm bridge cameras

More detail on the battle between Nikon and Canon for Auto Focus Dominance can be found in a short separate article. Regardless, manual focus cameras quickly became a niche product and Nikon’s final offering was the FM3A, with its 1/4000 second hybrid mechanical/electronic shutter.

Afterword – The Nikon FE10

There is a later Nikon with an FE designation. However, it was not a successor model to the FE and FE2 as it was built on a different chassis and designed for a different market. The Nikon FE10 of 1996 is a manual focus, F-mount film SLR manufactured under license by Cosina. It has a rather unappealing ABS plastic body in champagne silver and black body and was designed as a low cost beginner’s camera based on Cosina’s C2/C3 SLRs.

As such is unlikely to appeal to FE and FE2 owners, but Nikon’s fingerprints can be seen all over the enhancements to the donor Cosina. Depth-of field preview, AE Lock and exposure compensation, to name just a few, are features that make it usable by more experienced photographers. As a result it has some positive reviews from those that appreciate its light weight and very low cost.

Conclusion

I really enjoy shooting with the Nikon FE2 – it offers a very similar experience to the FM3A, a favourite of mine. It is both easy and rewarding to shoot with, and as it’s less of a collector’s piece than the FM3A, it’s one you can take anywhere.

Thoughts and Further Reading

If have experiences to share with the Nikon FE2, please leave me a comment below. I’d be delighted to hear from you. And if you are interested in classic or vintage cameras, there are articles on this site on:

- The Nikon F – Nikon’s first SLR

- The Nikon FE

- The Nikon F3 Pro Camera

- The Nikon FM3A – Nikon’s last manual SLR

- The Nikon F6 – Nikon last film camera

- The Leica M3 – Leica’s legendary rangefinder

- The Konica I – Konica’s first rangefinder

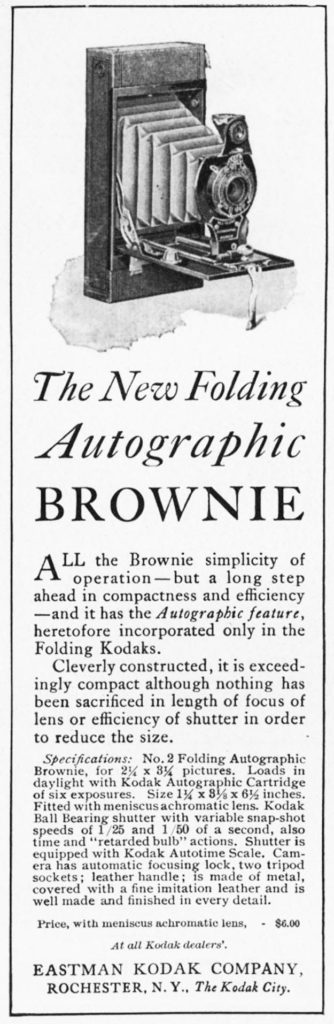

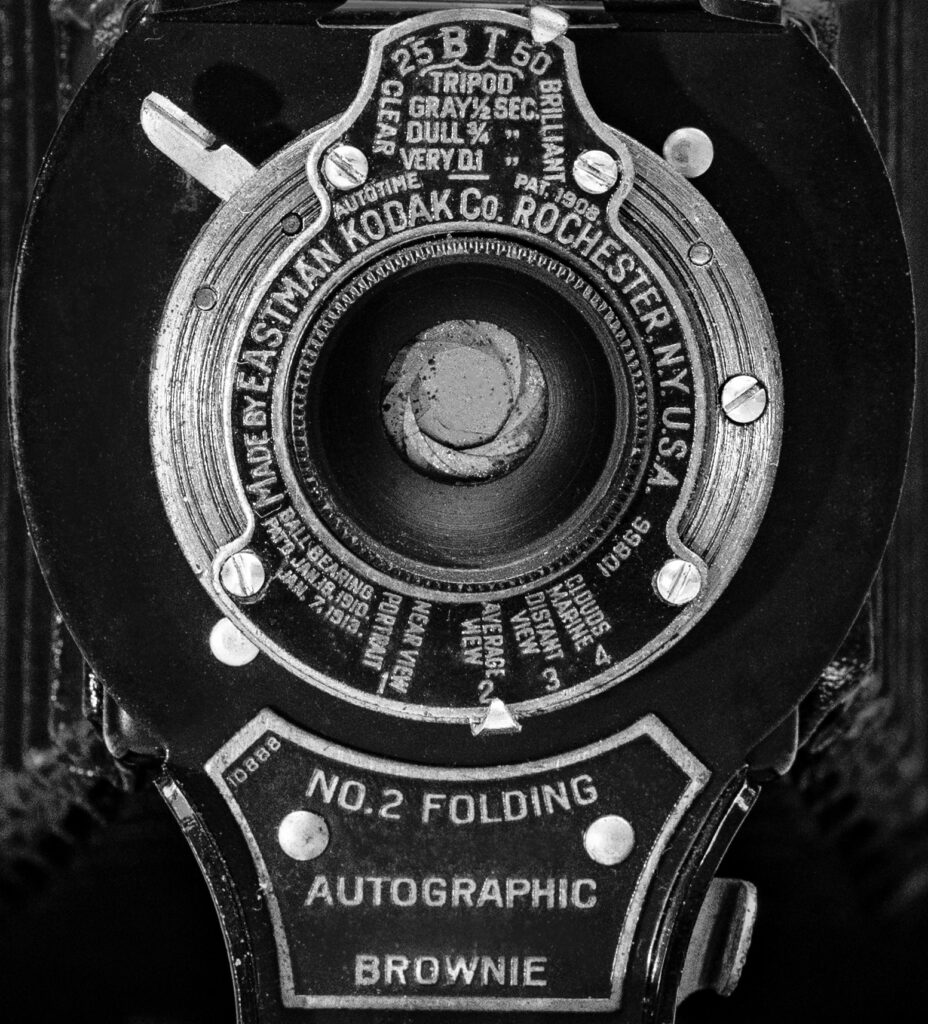

- The Kodak Folding No 2 Autographic Brownie

- Fox Talbot and Early Photography

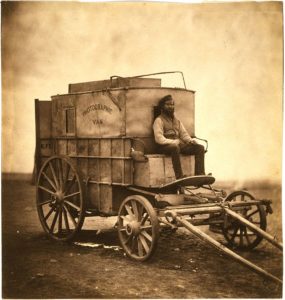

- Wet Plate Photography

- From Chemistry to Computation (Photography timeline)

- Pictorialism

- Timeline of Early Cameras

If you’ve any experience with the Nikon FE2, please leave me a note in the comments – I’d love to hear about it.

It’s been a while…

It’s been a while…

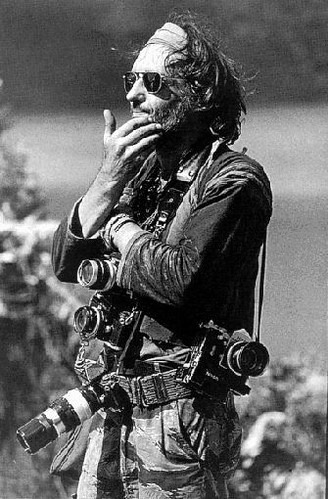

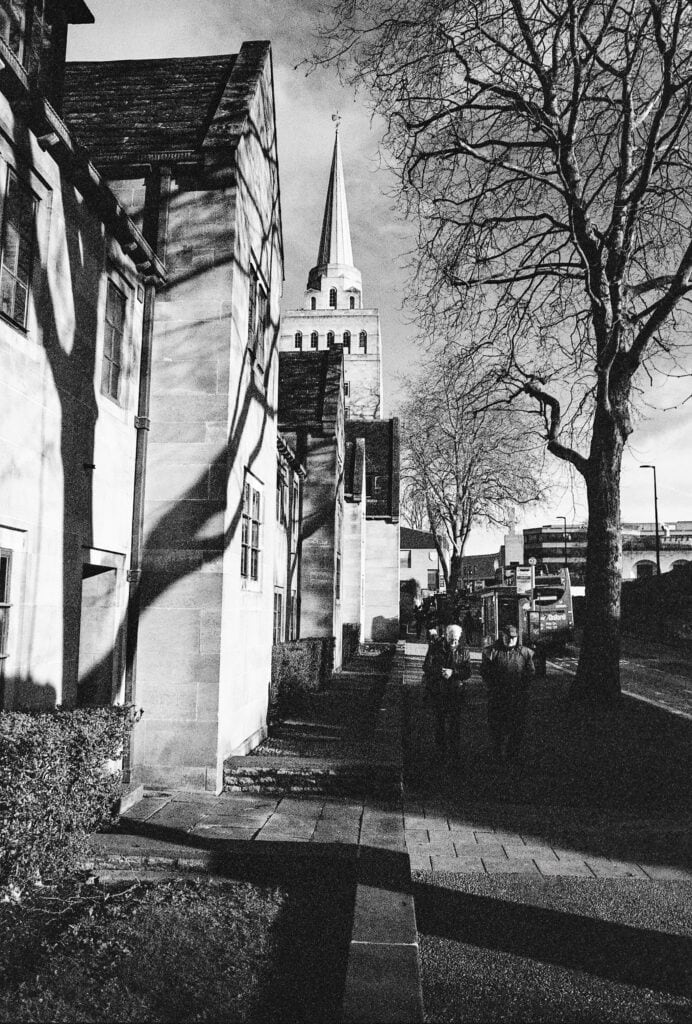

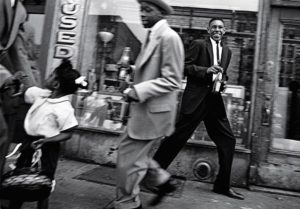

This is the oldest picture on this website and the beginning of my black and white photography journey.

This is the oldest picture on this website and the beginning of my black and white photography journey.