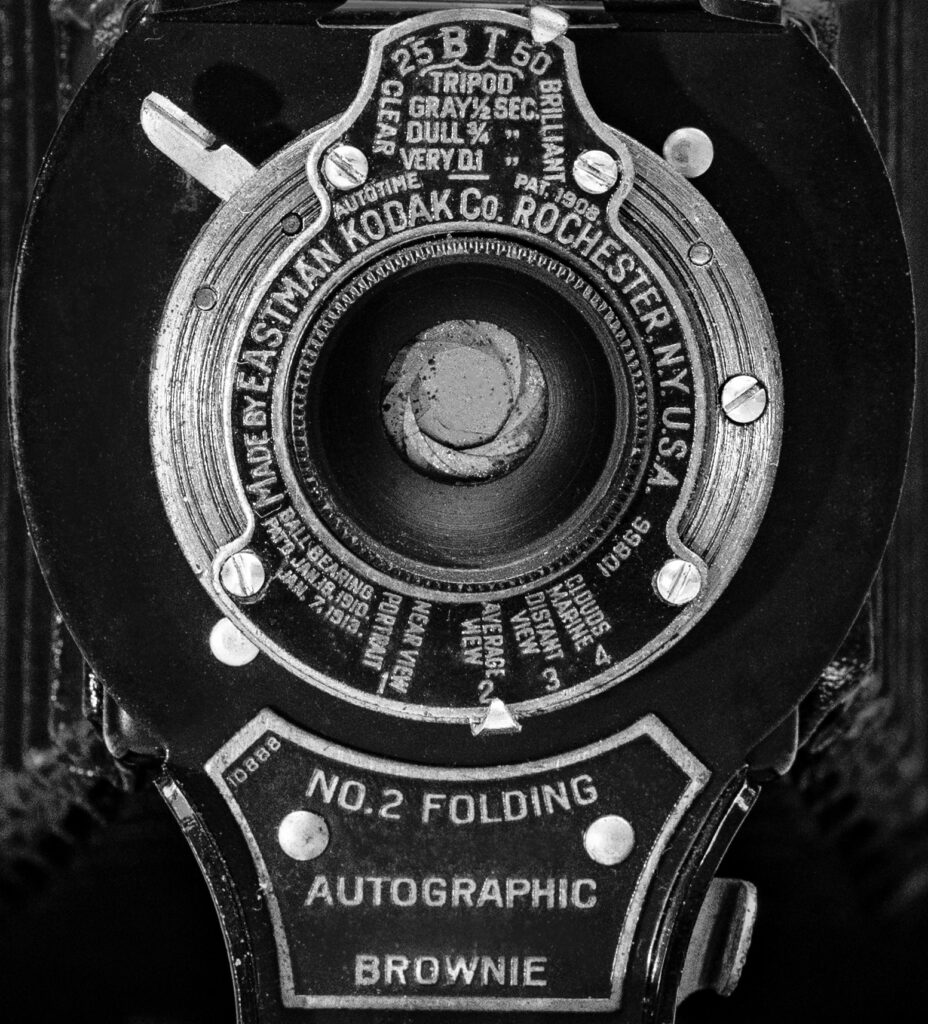

The Kodak No 2 Folding Autographic Brownie has couple of unique points of interest. The front plate is engraved with tiny text that describes the rather eccentric ‘Autotime’ system, and there is a stylus on the back to engrave notes on the negative using the Autographic feature.

It also has a good deal of ‘early camera’ DNA. Not only is the lens standard pulled out on a track fixed to the baseboard like a Victorian field camera, but the back is detachable, though it takes 120 roll film rather than a plate. This makes it one of the most interesting cameras I have ever come across, which inspired me to research and write this article.

From the serial number (109947) engraved on the foot this particular Kodak No 2 Folding Autographic Brownie was probably manufactured in late 1916.

For cameras made between 1915 and 1919 you can determine the date of manufacture of this camera with reasonable precision from the design changes listed by serial number at brownie-camera.com.

Serviced by Kodak in 1953

I bought it at a camera fair hosted by ImageX in Bicester, Oxfordshire and when I opened the camera up I discovered a Kodak London service sticker from 1953, proving it had a very long shooting life. Although the body shows quite a lot of wear and the aperture blades and shutter are slightly pitted, the camera is light-tight and in working condition – no doubt due to the care of attention of Kodak London.

Kodak’s Folding Cameras

This model of Brownie is a vertical format folding camera. Folding cameras originated in the 1850s, replacing the 1840s sliding-box design with leather bellows. See the article Early Cameras, a Timeline on this site for more on early camera design.

Kodak produced numerous folding models from the 1890’s until the 1960s. The first was the Folding Pocket Kodak which was introduced in 1897. The last was the Kodak 66, Kodak’s only post-war folder for 120 film rolls, which was manufactured in the UK between 1958 & 1960.

The non-box Brownies

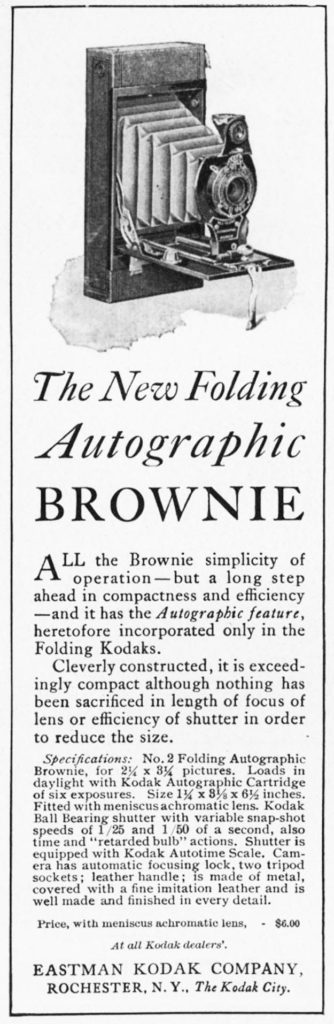

The name ‘Brownie’ brings a low-cost box camera to mind, but Kodak manufactured several folding models in that famous and long-lived family of cameras between 1904 and 1926. The Folding Brownie series were Kodak’s least expensive folding roll film cameras and had a more basic specification than their Kodak branded counterparts. The also offered fewer optional configurations.

The first folding Brownie was the No. 2 Folding Brownie, which was introduced in 1904, with a model B introduced in 1907 as the Folding Pocket Brownie. These were the predecessors of the Autographic Brownies.

The No.2 Autographic Folding Brownie

The No 2 model in Kodak Autographic Folding Brownie series was produced from 1915-1926 for the type 120 Autographic film. The exact number of cameras manufactured of this type in that 11-year period isn’t known, but brownie-camera.com states that 540,000 were made before 1921. Kodak only made minor changes to the design during the production run.

The most notable of these changes is the early change from the square-ended box shape shown in the Kodak Advertisement. This was changed to a more to a more curved design in 1917 (from serial no 133,301 according to brownie-camera.com.) Another change that is useful in dating models is the shape of the foot, which was modified from an S-shape to a C-curve in 1919 (from serial no 133,301 according to the same source).

120 Roll Film Format – The Last Survivor

Kodak produced a huge number of different roll film formats with a variety of different negative sizes. 120 (or No.2 film as it was originally called, as per the name of this camera) is the only one still being manufactured. The larger 116 and 130 film utilised by other Autographic Brownie models have both been discontinued.

120 film is still used extensively by medium format photographers, and readily available. The No 2 Folding Autographic produces 8 exposures measuring 6 x 9 cm, which are the largest that can be obtained with 120 film.

6 X 9 is a less common format than 6 x 7 (e.g. the hallowed Pentax 67), 6 x 4.5 (e.g. Mamiya or Pentax 645 models) or 6 x 6 (e.g the legendary Rolleiflex). Some examples of 6 x 9 cameras include the Fuji GW690 series, Zeiss Super-Ikonta C, Plaubel 69W ProShift, Royer Teleroy and Agfa Record III. Some technical and field cameras can also take 6 x 9 film backs.

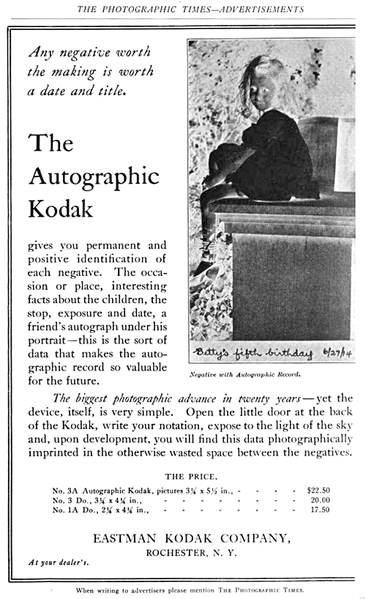

The Kodak Autographic System

Kodak was researching a way to allow the photographer to enter their own notes onto a negative when Henry Jacques Gaisman’s invention came to the company’s attention. ‘Jack’ Gaisman (1869 –1974) was a prolific inventor and the founder of the AutoStrop Company, a safety razor manufacturer. His patent was purchased for the sum of $300,000. It was such a large amount at the time to as to be newsworthy and the purchase was covered in the New York Times. Gaisman reputedly filed over one thousand patents including those related to swivel chairs, men’s belts, and carburettors, as well as razors and cameras.

The Kodak Autographic System uses a narrow slot covered by a light-tight hatch. To write a note, the user lifted the hatch, which revealed the film’s paper backing. A stylus held by a clip on the back of the camera next to the hatch was used to make a notation on the paper backing. The hatch was left open for a few seconds, depending on the prevailing light, which exposed the marked area and burned the note in. The text entered would appear in the margin of the processed print

Kodak’s autographic films (which were designated by an ‘A’ after the film size designation) made use of thin carbon paper sandwiched between the film and the paper backing.

Other Autographic Models

There were two other models of Folding Autographic: the No 2A for the slightly larger 116 film, and the No 2C for 130 film, which produced the largest negatives. Kodak sold autographic backs as upgrades for their existing cameras.

Autographic Advertising

The Kodak autographic was hailed in the original 1915 advertisement as ‘The biggest photographic advance in twenty years’. Kodak also promoted the Autographic with the slogan shown in the advertisement below: ‘Any negative worth the making is worth a date and title’.

Despite Kodak’s promotional efforts the system was never popular. It was discontinued in 1932.

You can read Kodak’s account of the benefits of autographic photography, from the 1915 ‘Kodaks and Kodak Supplies‘ here.

Lens Options and Shutter Variants

There was a choice of two lenses. The higher end lens option is a rapid rectilinear which was widely used in more expensive cameras. The other is a very simple achromatic lens. They are easy to distinguish as the glass elements the achromatic lens are behind the shutter and the aperture.

Information on the focal length of either lens is hard to come by, but I have seen a reference to 98mm and a maximum aperture of f/7.9. Given the crop factor of a 6×9 image the 35mm equivalent is approximately 42mm, which is what I would expect from the shots I have taken.

Both lenses made use of the quirky and not particularly accurate Kodak ball bearing shutter until it was replaced in the last two years of manufacture by a Kodex shutter.

Shutter speeds are limited to 1/50 seconds and 1/25 seconds plus B (Bulb) and T (Time) for long exposures. In keeping with the rest of the camera, the shutter speed selection scale is rather eccentric with the B and T modes set between the ‘instant’ speeds.

The Autotime System

The Kodak Autographic System isn’t the only Kodak innovation on the camera. Setting the correct exposures was originally performed using the Kodak Autotime system, an early, and rather incomplete, automation system.

Using Autotime, the photographer selects the shutter speed to match the lighting conditions. The 1/50th second speed is marked “Brilliant” 1/25th “Clear” and guidance for “Gray”, “Dull” and “Very Dull” is marked in between. These make use of the slower, and manually, controlled Bulb and Time settings. Aperture selection using Autotime is via a choice of subjects marked at the bottom of the shutter dial. These are “Portrait/Near View”, “Average View”, “Distant View”, “Clouds/Marine”.

The Autotime Patent

Autotime was patented in 1908. It was not a Kodak invention, nor was the idea fully implemented as it lacked the mechanically geared linkage between aperture and speed settings suggested by the inventor, Frank S. Andrews. I can find little about the visionary Mr Andrews except in this article on the Autotime scale. The concept was well ahead of its time, and it was not until the 1950’s that the coupling of aperture and speed settings was resurrected by Kodak in the Retina range of 35mm cameras.

The Autotime Scale was eventually abandoned along with the Autographic feature.

The 1-4 Aperture Scale

Below the Autotime labels are the numbers 1-4. These are from a simple 1-4 scale often used on low cost Kodak cameras. This can be confused with the U.S. Universal Scale System, also called the “Uniform Scale System”, often used on simple cameras prior to 1920. See the article Aperture Scales on this site for more on this.

The 1-4 numbers on this camera represent f/8, f/16, f/32, and f/64.

The No2 Kodak Autographic Folder in Use

My example has the simple lens option so my expectations from camera weren’t high, but I was pleasantly surprised by the results. I didn’t experience any of the light leaks that often plague cameras of this vintage, presumably because the bellows were replaced during the 1953 service – they are in excellent condition. The focus was reasonably sharp and the exposures fairly accurate.

Framing and Focusing

Framing isn’t easy as it relies on the tiny (1.5 cm x 1.5 cm) ‘Brilliant’ finder mounted above the lens. This creates a tiny and approximate representation of what the camera is pointing at. Peering down into the minute square of glass the photographer sees an image that is laterally reversed just like a viewfinder in a Rolleiflex, but much, much smaller! It is usable, though getting the horizon level isn’t easy.

Focus is very basic ‘scale focusing’ and is set via a scale on baseboard. This has just two pre-set distances that engage with a catch on side of the lens standard. I’ve only ever used the most distant of these (30m or 100 feet). I’ll get round to trying to shoot some portraits at some point and try out the 2.5m/8 feet setting.

Setting an Exposure

Setting an exposure isn’t difficult as there aren’t that many usable options! I always use 1/50th of a second as the 1/25th is a bit slow without a tripod, and I avoid setting the aperture wide open as this is likely to be when the rather unsophisticated lens will produce the softest image. This gives me a fixed shutter speed and a choice of 3 apertures, which I select after consulting the light meter on my iPhone. Given how forgiving black and white film is in terms of exposure latitude, I haven’t found it difficult to get a reasonably accurate exposure.

The shot above left was taken on a cloudy day with Kodak TMAX 100. I had to crop it as the horizon wasn’t straight. It is by no means a great shot of a wonderful location, but it does prove the Kodak to be surprisingly effective. I have a gallery of shots of the manor and you can also read about the story of the ruined manor and the lost village of Hampton Gay.

The shot below right was taken with same film from the first roll I shot from the pier in Deal, Kent. The shot is reasonably sharp and the image is uncropped as I managed to get the horizon straight. There is a dark patch in the centre of the sky, though I am not quite sure what caused it. This was evident in a couple of other shots from that roll. There are several galleries on Deal on this site.

Avoiding Film Fogging

Care needs to be taken of the red frame counter window on the back of the camera, which displays the frame counter numbers on the backing paper of the film. Early film had low sensitivity to red light so a combination of the backing paper on the film, plus the red window, prevented film fogging. Modern film is sensitive across the whole spectrum of light, so taping up the window whilst it is not in use helps prevent light getting into the camera. I haven’t experienced any fogging by removing the low tack tape I use to view the film counter when winding on, so it doesn’t present a real problem. This is similar to later frame counter windows that had little covers to prevent light leaks and were only opened whilst the photographer was advancing the film.

Some reviewers have developed workarounds for winding on ‘blind’ with the tape applied throughout but I haven’t found that necessary.

Loading and Unloading

Loading the camera with film isn’t especially difficult – I used this YouTube video to help me the first time round. I have found that my camera won’t wind on past frame 8, but I work round that by unloading the camera in darkness, and haven’t lost any frames as a result.

Getting in Touch and Further Reading

If you’ve any experience with the Kodak No 2 Autographic Folding Brownie, please leave me a note in the comments – I’d love to hear about it.

If you are interested in the history of photography, you might enjoy these articles on this site.

- Fox Talbot and Early Photography

- Wet Plate Photography

- The First Camera Lens

- The Kodak No 2 Folding Pocket Brownie

- From Chemistry to Computation (Photography timeline)

- Pictorialism

- Timeline of Early Cameras

- The Nikon F3 Pro Camera

- The Nikon FM3A – Nikon’s last manual SLR

- The Nikon F6 – Nikon last film camera