It’s hard not be distracted from Vivian Maier’s work by her life. As told in the 2015 documentary Finding Vivian Maier, the extraordinary stories of her life and the discovery of her work have contributed substantially to her posthumous status as a photographic legend.

Taking in the first UK exhibition of her work Vivian Maier: Anthology, in Milton Keynes, I was determined to avoid that. Vivian Maier’s work demands our full attention.

As Enigmatic as the Smile of the Mona Lisa

The challenge of admiring Vivian Maier’s work is that her life story is so unusual and her work so deeply entwined in it, that it is extremely difficult not to get lost in it. Her experimental self portraits, frequently cast in shadow or captured in a reflection, contribute to this challenge. Sometimes they are playful, often slightly mischievous and occasionally ghostly, but every glimpse draws you into the life of an extraordinary woman. Her appearance is as enigmatic as the smile of Mona Lisa and it’s hard not be fascinated by her and dwell on her extraordinary story.

The White Bear

Not dwelling on Vivian Maier’s life story when looking at her work is so difficult that it reminds me of the famous test of the white bear. As a boy, Tolstoy and his friends founded a club with the sole membership requirement of standing in a corner for 30 minutes and not thinking about a white bear. This is called intentional thought suppression, and it is difficult to achieve. There is a book on the subject: White Bears and Other Unwanted Thoughts.

A Guardian review of Anthology argues that the exhibition of 146 images overcomes this problem, and I agree. ‘The extraordinary life story of the nanny who was secretly a street photographer can overshadow her groundbreaking images – but at the first UK show of her work they take spectacular centre stage’ was Sean O’Hagan’s summary.

The text that greeted me on the wall of the Anthology exhibition by curator Anne Morin described her life in just 75 words.

Vivian Maier’s work was unknown to most people for the vast majority of her life. While working as a nanny in New York and Chicago for over 40 years, she photographed daily life on the streets. She produced over 140,000 images as well as film and audio recordings. Maier’s work came to light in 2007, just before her death, when her huge archive was auctioned off from a Chicago storage locker due to missed payments.

Vivian Maier: Anthology, Milton Keynes, June-September 2022, curated by Ann Morin

I’ll leave it at that. Morin’s introduction, captured by my iPhone, then went on to describe her work.

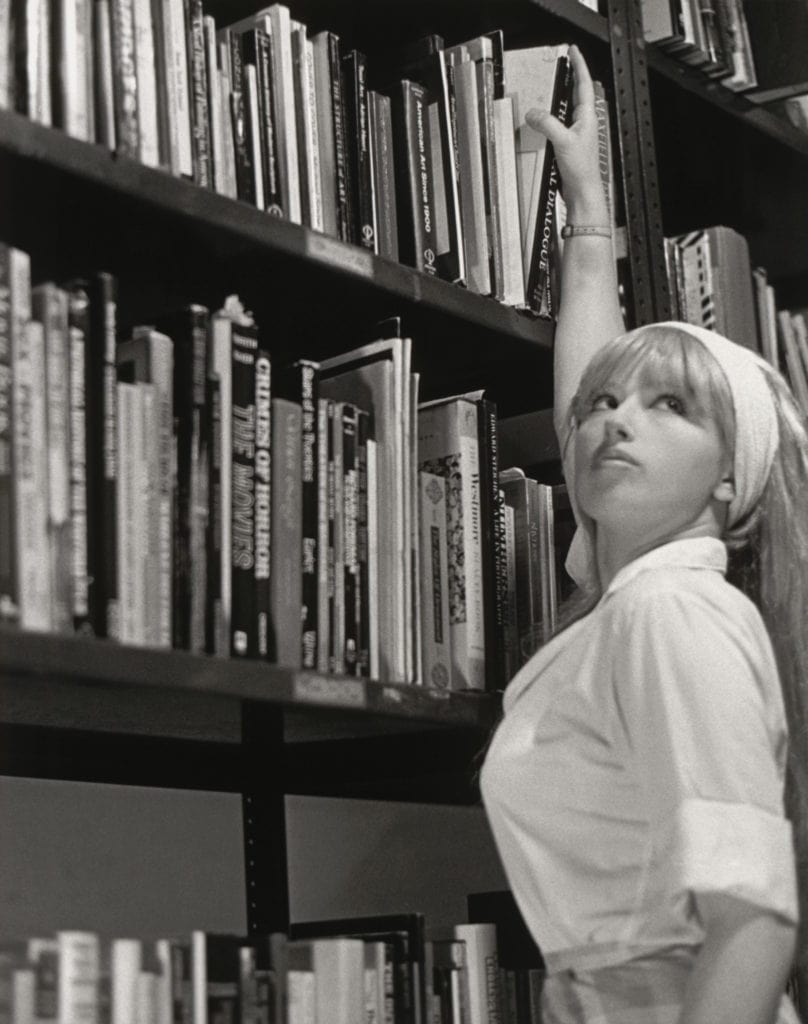

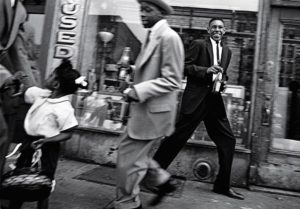

Her images, mostly from the 1950s – 1970s, present a distinctive record of urban America. From carefree children and glamorous housewives to the homeless and poor, Maier’s pictures capture the highs and lows of everyday life. Street scenes with shop fronts, arcades and architectural images play with perspectives and patterns. Smouldering furniture, abandoned toys and tangles of electrical cables set the scene as families, workers and commuters go about their daily business.

Vivian Maier: Anthology, Milton Keynes, June-September 2022, curated by Ann Morin

The Exhibition

Up close to the large prints of the exhibition, Vivian Maier’s work made a huge impression on me. I am reasonably well versed in the history of photography and have written about several of the greats that stopped me in my tracks: Fan Ho; William Klein; Brassai and Cindy Sherman amongst them. Artists sometimes have the same effect. Caravaggio, the original master of dark and light, is one who took my breath away. Maier is one of these – the kind of photographer who inspires you to pore over books of their work (I bought the Thames and Hudson retrospective).

What struck me about Vivian Maier’s work, particularly her square framed black and white street photography, is the unique combination of ‘how did she do that?’ composition, shot making excellence and an extraordinary probing empathy for her subjects.

The strange, rather detached, but still evident humanity that characterises Maier’s street photography work is arresting. In another Guardian review Adrian Seattle concludes with ‘We could talk of a compassionate eye but I’m not sure it helps or even if it is true. It was all the same to Maier and she didn’t flinch or pass by.’ The autobiography Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny by Ann Marks records that Maier was once described as an extraterrestrial by an acquaintance, and I think I understand why. There’s that white bear again.

Vivian Maier’s Cameras

Much of the exhibition shows images taken on the iconic 6 x 6 medium format Rolleiflex, for which Maier is most famous. A little online research revealed that, like many photographers of the period, she started out with a simple Kodak Brownie box camera. Maier acquired her first Rolleiflex in the early 50’s and over the course of her career used a Rolleiflex 3.5T, Rolleiflex 3.5F, Rolleiflex 2.8C and a Rolleiflex Automat. The Rolleiflex is solidly made and weighty, with the 3.5F tipping the scales at over 1.2 Kg.

The Iconic Rolleiflex

The Rolleiflex is a twin-lens reflex camera (TLR) which has two lenses with same focal length, one above the other. The bottom lens is used to take the picture, while the top lens is used for viewing the image. The two lenses are connected, so that the focusing screen displays what will be captured on film. Because the camera is held or suspended at waist level the viewfinder is often called a ‘waist level finder’. That viewpoint is quite different, and subjectively often better than an eye level view, simply because it is lower.

The viewfinder requires an angled mirror to reflect the image onto a matte focusing screen at the top of the camera, which the photographer looks down into. Unlike an SLR, in which the mirror moves out of the way when the shutter button is pushed, the mirror remains stationary. The advantage of this is that there is no ‘mirror slap’ or vibration from the mirror as it moves. This allows the Rolleiflex to shoot at lower shutter speeds hand-held.

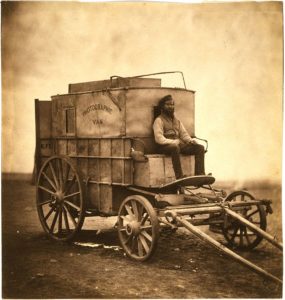

The first TLR model is not known for certain, but the London Stereoscopic Company’s “Twin Lens Carlton Hand Camera”, from 1898, is a good contender. Mass adoption came later however, with the introduction of the Rolleiflex in 1929, developed by Franke & Heidecke in Germany.

Other Rolleiflex Users

Vivian Maier is one of the most famous Rolleiflex photographers. Other illustrious users include Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, David Bailey, Bill Brandt, Robert Capa, Imogen Cunningham, Robert Doisneau, Helmut Newton and Gordon Parks. Amateur users included celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, James Dean and Grace Kelly.

Post Rolleiflex

Post Rolleiflex, Maier embraced the freedom a 35mm camera can provide, wielding a much more compact Leica IIIc rangefinder, an Ihagee Exacta SLR, (star of Hitchock’s Rear Window) a Zeiss Contarex SLR and a few other SLR models. Maier mostly used Kodak Tri-X black and white film, which was introduced in 120 form in 1954, and from the early 70s onwards Ektachrome colour film.

Shooting with the Rolleiflex 3.5F

I have a Rolleiflex 3.5F Twin Lens Reflex (TLR). It is a beautifully engineered camera and the view of the world is much improved through its ground glass screen. It really is magical. Achieving critical focus at wider apertures isn’t easy, however, and the Selenium light meter isn’t particularly accurate. The maximum speed the leaf shutter can deliver is 1/500 of a second. When you first use a Rolleiflex the lateral inversion and odd viewpoint can make you dizzy. Because of a balance problem, I’ve never quite conquered that.

To get the same beautiful waist-level view, but with a higher percentage of keepers and less dizziness, I have shifted my medium format allegiance to a Hasselblad 203FE, which is an SLR with a waist level finder. I have no idea why such a similar shooting experience doesn’t affect my balance. However, in terms of both usability and keepers, the Hasselblad’s almost supernatural light meter, auto exposure, astonishingly bright acute matte viewfinder and 1/2000 second focal plane shutter make its complexity worthwhile. Now and again I dust off my Rolleiflex and venture out with it, but as yet I have no images to cherish from those forays, but I haven’t given up.

I have no idea what percentage of keepers Vivian Maier had – and at this point, whilst her vast body of over 100,000 images is still being curated, (there’s the white bear again) I imagine even the archive manager of the biggest collection, John Maloof, doesn’t have the full picture yet, but every image I’ve seen is superbly executed. She clearly knew her craft very well indeed.

Colour Photography

In Chicago in the early 1970s Maier switched to colour photography, shooting with a Leica IIIc rangefinder and various German SLRs. 35mm rangefinders and SLRs typically have eye level viewfinders and the change of viewpoint from waist level to eye level is a significant shift. Some of the work from this period seems to be as much about exploring colour as depicting the subject, and there are also less people and more objects, including found objects. I enjoyed the images, but my preference is for the earlier black and white square-framed Rolleiflex shots.

Vivian Maier’s Time Capsule

Much like opening up a time capsule, viewing her work makes you feel like a time traveller. Immersed in each piece of work, a glimpse into the life and times of a bygone era. Maier was ahead of her time; her images are timeless. Her empathic eye made her street portraits striking. Her images portray a great deal of affection toward her subjects. She had the knack for capturing the essence of her subjects. Vivian had a gift for entering the privacy of the people she photographed; her brilliance in reading human behaviour is undeniable. Like a movie trailer, her photographs leave us with more questions than answers. Cleverly timed. Always in the right place at the right time, with an intuitive sense of timing, effortlessly capturing moments of both high drama and sublime banality. It is not easy to make the mundane and everyday look extraordinary, but Vivian did with an expert sense of composition.

Vivian Maier: Anthology, Milton Keynes, June-September 2022, curated by Ann Morin

That sense of time travel is something only the greats can deliver. I had the same sensation when I came across the work of Brassai, who transported me to his dark and beautiful realm in 1930s Paris. Vivian Maier does the same for New York and Chicago from the ’50’s to the 70’s, delivering a head-shaking ‘how does she do that?’ experience, both in terms of her composition and crisp shot taking.

To be able to conjure up that sense of wonder and to transport us to another time and another place is a rare thing and I am grateful to the enigmatic woman who made it possible. And if that troublesome white bear sometimes intrudes, that’s a price worth paying.