The village of Hampton Gay has largely disappeared, leaving only an isolated church and the picturesque ruins of an Elizabethan manor house. The remaining inhabitants reside in the farmhouse and cottages that line the last few yards of single track road; a mile long, single track spur that connects to the road from nearby Hampton Poyle and Bletchingdon. Once you pass though the pedestrian gate into the fields you can see the outlines of where Saxon dwellings once were from the humps in the grass.

Finding Hampton Gay

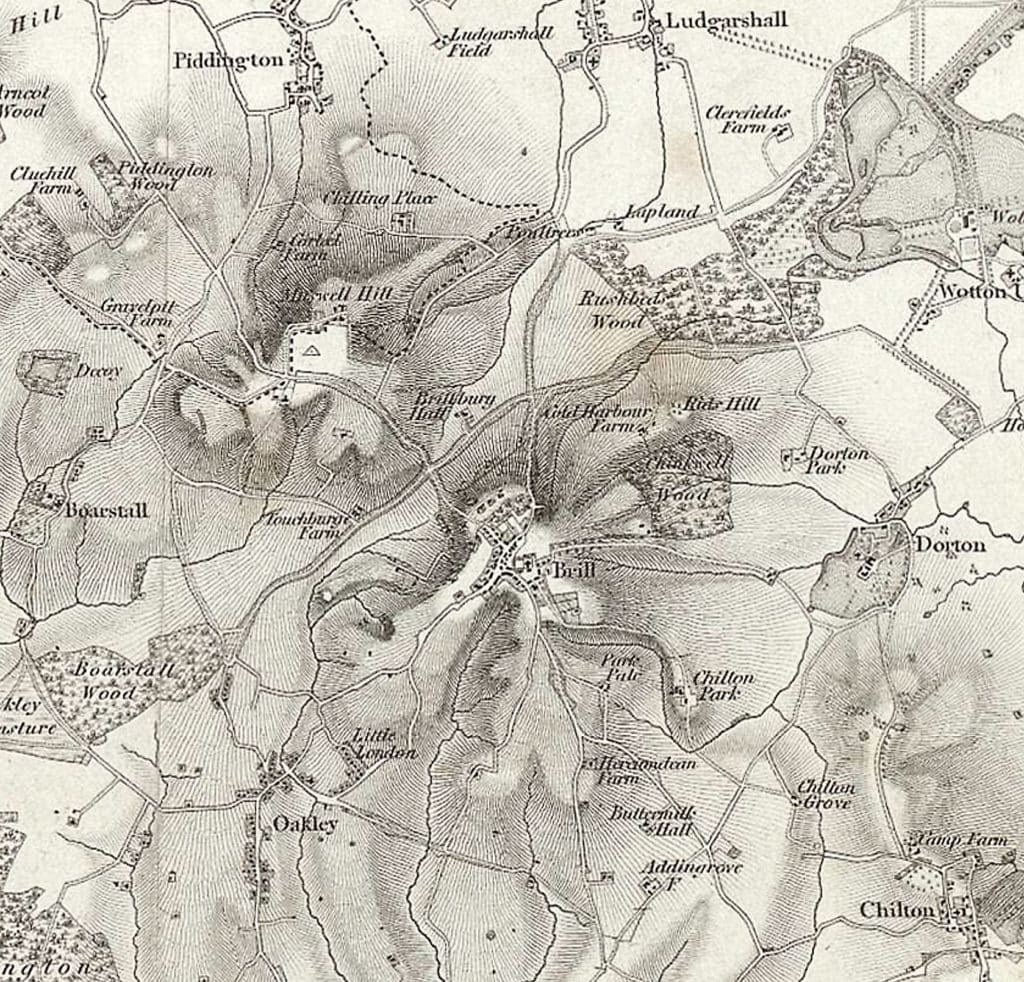

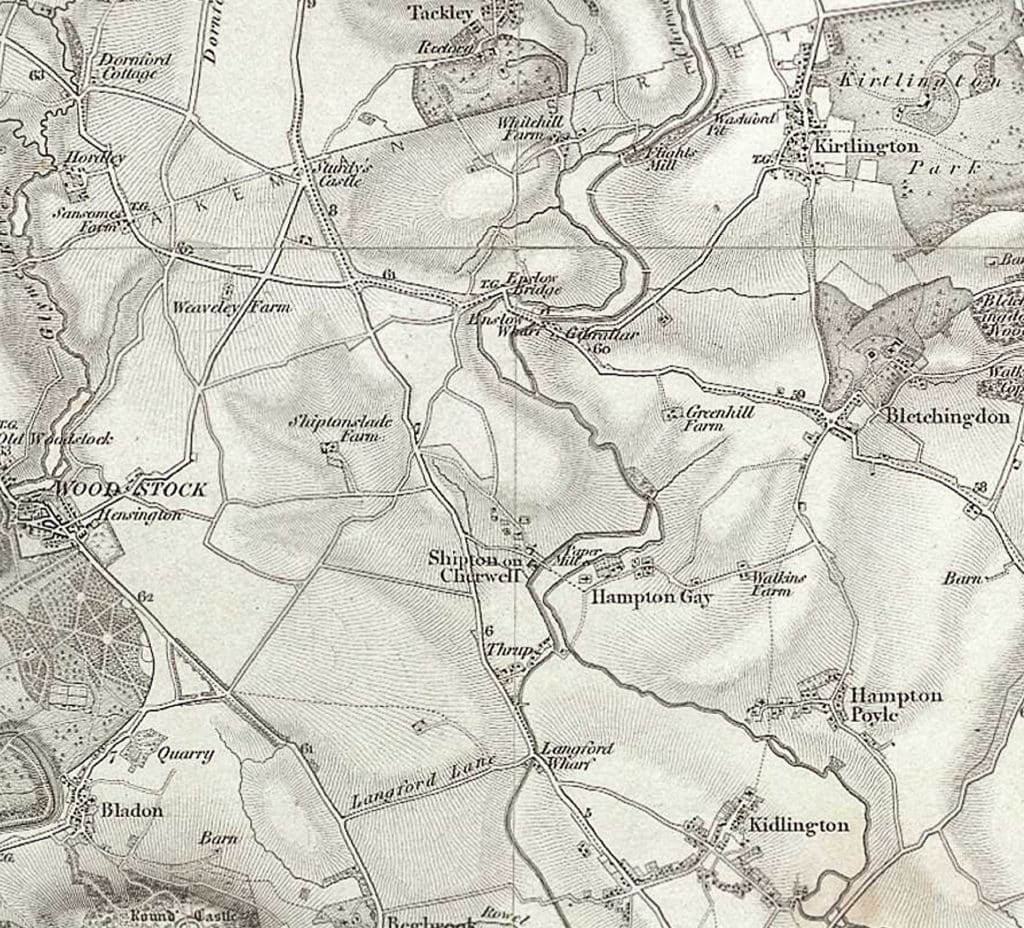

Hampton Gay is an ancient spot and much of the surrounding farmland on the nearby circular walk undulates as a result of the use of the mould-board plough in medieval times. The best way to see it is to walk from Thrupp, a small village just north of Kidlington, and along the canal to Shipton-on-Cherwell. There you turn right across a bridge over the river Cherwell and arrive at Hampton Gay after a few minutes walk. It can also be reached by on a circular walk from the excellent Bell pub in Hampton Poyle.

By car you’ll need to take the single-track spur road. There are a few passing places but there is a blind bend just past Willowbrook Farm, so please drive slowly and carefully.

I’ve been visiting and photographing the ruin for many years with all kinds of cameras; a 1916 Kodak, a Rolleiflex 3.5F, a Leica M3 and late model film cameras such as the Nikon F6 and Hasselblad 203FE, as well as one or two digital models. The aspect of the ruins changes greatly according to the season and the light, which makes it well worth a return visit. You can find my photography galleries from those visits at the links below. Most of the shots are in the main gallery with smaller selections in the following two.

Village origins

The de Gay family were tenants of the two estates in Hampton Gay in the 12th and 13th centuries – the village name combines their surname with the Old English for a village or farm. The de Gays donated and sold land from the estate to various religious orders including the ill-fated Knights Templars, the Abbey of Osney, just outside Oxford’s west gate, and the Convent at Godstow.

The manor house at Hampton Gay

All the land owned by religious orders at Hampton Gay were forfeited after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The crown sold the land into private ownership and in 1544 it was purchased by John Barry, a wealthy glover turned sheep farmer from Eynesham. After John died, the manor passed to his son Laurence and then to his grandson Vincent, who built the Manor – probably in the 1580s. In 1682 the Barrys mortgaged the manor and then sold it to Sir Richard Wenman of Caswell and in 1691 his widow Katherine sold the manor to William Hindes. The story of the Barry family at Hampton Gay from the the 16th to the 20th century is an interesting one that I’ve researched. You can read their story here.

The Manor remained in the Hindes family until until 1798. It changed hands again in 1809 and 1849, and in 1862 was bought by Wadham College, Oxford. The full list of owners over the years can be found here.

The Manor House was constructed to the classic Elizabethan E-shaped plan with gabled wings and a crenellated central porch. The vertical line of the E was the main hall, and the horizontal end lines the kitchens and living rooms. The central line was the entry porch.

As late as 1870, the building was still largely original including oak panelling, though it had been neglected. By 1809 it was reported to be a ‘Gothic manor’ in a neglected state and in 1880s the house was divided into two tenements which were jointly occupied by a farmer and Messrs. J. and B. New, paper manufacturers.

The Fire at the Manor

In 1887 it was gutted by fire and has never been restored.

Some images of the manor before the fire survive. The architect John Chessell Buckler (1793-1894) recorded many historic buildings in great detail, especially in Oxford and Oxfordshire. This included a fine drawing of the Manor at Hampton Gay in 1822 The original is now in the Bodleian Library. There is also a steel engraving by Joseph Skelton in Skelton’s Oxfordshire.

Return of the Barrys

The manor returned to the Barry family in 1928 when Wadham college sold the ruin to Colonel S.L. Barry of Long Crendon, a descendant of the Barrys who built it. Colonel Barry (1873-1943) was a highly decorated soldier who served in the Boer War and World War One. His military appointments and civil posts included membership of His Majesty’s Bodyguard and The Honourable Corps of Gentlemen-at-Arms, Deputy Lieutenant of Oxfordshire, Justice of the Peace for Buckinghamshire, High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire and Lord of the Manor of Long Crendon, Bucks, and Hampton Gay, Oxon. Colonel Barry’s papers (now deposited at the Oxford History Centre) reveal that during the 1920s and 1930s he compiled research notes, photographs and transcribed deeds, covering the history of the manor and its ownership.

Two mills and three fires

There has been water mill at Hampton Gay on the River Cherwell since the 13th century. It was a grain mill until 1681 when it was converted into a paper mill. The nineteenth century was a particularly eventful time for the mill.

In 1812 continuous paper making equipment was installed. Between 1863 and 1873 it underwent reconstruction, but two years after that work was completed it was destroyed by fire. It was rebuilt and then re-roofed in 1876. By 1880 it had both a water wheel powered by the river and a steam engine and was capable of producing a ton of paper per day. It closed in 1887 after a second fire. That same year, a third fire consumed the manor house. After the fire at the manor, the owners sold the mill and its remaining stock to pay the rent. Some time after 1887 it was demolished. Some remains and waterways still remain.

The train crash

There were rumours that the manor was deliberately burned down for the insurance. More imaginatively, others claimed it was the result of a curse related to one of the worst train accidents to take place on the Great Western Railway. On Christmas Eve 1874, a Great Western express train from Paddington was derailed on the nearby Cherwell line. Thirty-four people died in the accident and sixty-nine were injured.

Among those coming to the aid of the victims was Sir Randolph Churchill, father of Sir Winston, from nearby Blenheim Palace. The paper mill was used as a temporary mortuary, and the church a refuge against the bitter cold until a train arrived to take the injured to the Radcliffe Infirmary and the other survivors to Oxford hotels. According to the story, the residents of the manor house refused shelter to the victims and the curse was retribution for this.

The inquest

Hampton Gay Manor House was used to hold the inquest which opened two days after the accident. The bodies of the accident victims were held at the paper mill for identification and the wreckage was also examined. After the inquiry moved to Oxford the inquest found a tyre failure and braking problems to be the cause.

The agrarian revolt

Hampton Gay is known for its villager’s part in the unsucessful agrarian, or Oxfordshire rising, rising of 1596. The Barrys enclosed land at Hampton Gay for sheep pasture. The villagers, unable to till the land for their own produce, faced starvation and many joined a revolt. The plan was for the villagers to come together to murder Barry and his daughter, but this was foiled when the village carpenter turned informant. One of the ringleaders from the village received the barbaric sentence of being hanged, drawn and quartered. Subsequently, the Government recognised the cause of the rebels’ grievance and the Tillage Act of 1597 enabled the land to be ploughed and cultivated once again.

The church of St. Giles

The church of St. Giles now stands in picturesque isolation not far from the ruin of the manor house. It has never had electricity and is lit by candle light. Evidence of its existence dates to 1074 and it was granted to Oseney Abbey by the de Gay family about century later.

By the time of the dissolution it fallen into disrepair after which it became a free chapel, funded by the owners of the Manor. It was completely rebuilt in the eighteenth century in Georgian style by the owners and re-modelled in the nineteenth century using the Early English Gothic and Norman revival styles. Nothing remains of the medieval building except the cross on one of the gables and the reused battlements of the square tower. One of St. Giles’ two bells is from the mid-13th-century and is one of the oldest in the country.

Fluctuating fortunes

Hampton Gay’s population has fluctuated over the years in line with its fortunes. In the fourteenth century it had between nine and twelve taxpayers. In the fifteenth century it was exempted from taxation because there were fewer than ten resident householders. The Compton Census recorded twenty-eight adults in 1676. The population increased during the late 18th century – in 1811 there were seventeen families crowded into thirteen houses. The peak was reached in 1821, with eighty-six inhabitants, After the fire and mill closure in 1887 the population fell to thirty and by 1955 there were only fourteen parishioners. Hampton Gay ceased to be a separate civil parish in 1932 when it was merged with Hampton Poyle.

A strange occurrence

I updated this article, adding the Hampton Gay photo gallery, in June 2020. That week I came across a post that mentions a photographer observing something out of the ordinary at the ruin. I found that was curious and a little spooky, as I had seen exactly the same thing a few days previously, but never before. It was a heavy piece of black cloth, like a curtain, hanging from a second floor window and moving in the wind. It was only in view for a few seconds and I wasn’t able to photograph it, though the other photographer did. The black cloth later revealed itself to be a tarpaulin.

Renovation attempts

There have been several proposals to renovate the Manor. The earliest of these came in 1901 from the distinguished architect T.G. Jackson, famous for his remodelling of Victorian Oxford and whose work includes the iconic Bridge of Sighs.

In 1975 Jiri Fenton, of Oxford University’s department of experimental psychology, purchased the building from Colonel Barry’s daughter. His intention was to restore the Manor as a thank you to the nation for providing him a home when he fled the Nazis in 1939. His attempts failed due to “crippling inflation and Government red tape”, according to the Oxford Mail.

In 2010 Christopher Buxton, whose company Period and Country Houses restored and sub-divided English country houses, submitted plans to create a five-bedroom home within a concrete envelope that would support the original walls. He had also submitted plans four years previously, but neither plans proceeded.

2023/2024 Restoration

The winter of 2021 saw a noticeable decline in the fabric of the Manor with the large chimney stack on the West side of the building falling some time between late January and early April 2022. However, on a visit in May 2023 I observed scaffolding being erected and over the course of 2023 much work was done to stabilise the ruins. At my last visit in March 2024 the scaffolding was gone and the building was back to its ruined splendour.

The surroundings are also changing, with renovation of one of the old outbuildings and construction of new stone buildings. The work has been done sensitively and looks to be of a high standard but the surroundings of the manor no longer have the aspect of deserted parkland they once had.

Hampton Gay Today

The village of Hampton Gay is enjoying a resurgence in traditional (organic and natural) small scale farming. Manor Farm (whose ownership includes the ruins) and Willowbrook Farm are both passionate advocates for this and their efforts have boosted the population of the hamlet.

Manor Farm keeps a herd of English Longhorns who graze in the fields adjacent to the manor and sometimes on the banks of the Cherwell. Though the large curved horns that frame their faces make them look fearsome they are actually rather docile. The breed has a fascinating history. It became endangered until rescued in 1980 by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust. Since then, Longhorns have made a dramatic, and welcome, comeback.

Hampton Gay remains one of the most picturesque spots in Oxfordshire, set in a landscape that is ideal for country walks. The Bell in the nearby village of Hampton Poyle is an excellent hostelry to stop at for food en route or afterwards. There are three circular walks from The Bell, one of which goes to Hampton Gay. The walk is described as a ‘stroll across the meadows to an isolated church and ruined 16th-century manor house.’ and takes about 2 hours.