I have been photographing the ruined manor at Hampton Gay regularly over the last 20 years or so. Along the way I learned about the history of the manor, and became interested in the story of the family that built it. According to the landed families site the story of the Barry family at Hampton Gay starts with John Barry (d. 1546), a glover and landowner of Eynsham, Oxfordshire. The coat of arms of the Barry family dates back much earlier – to the reign of King Edward II (1307-1327) – but the connection to that time is no longer discernible.

Oxford, Sheep and the Manor

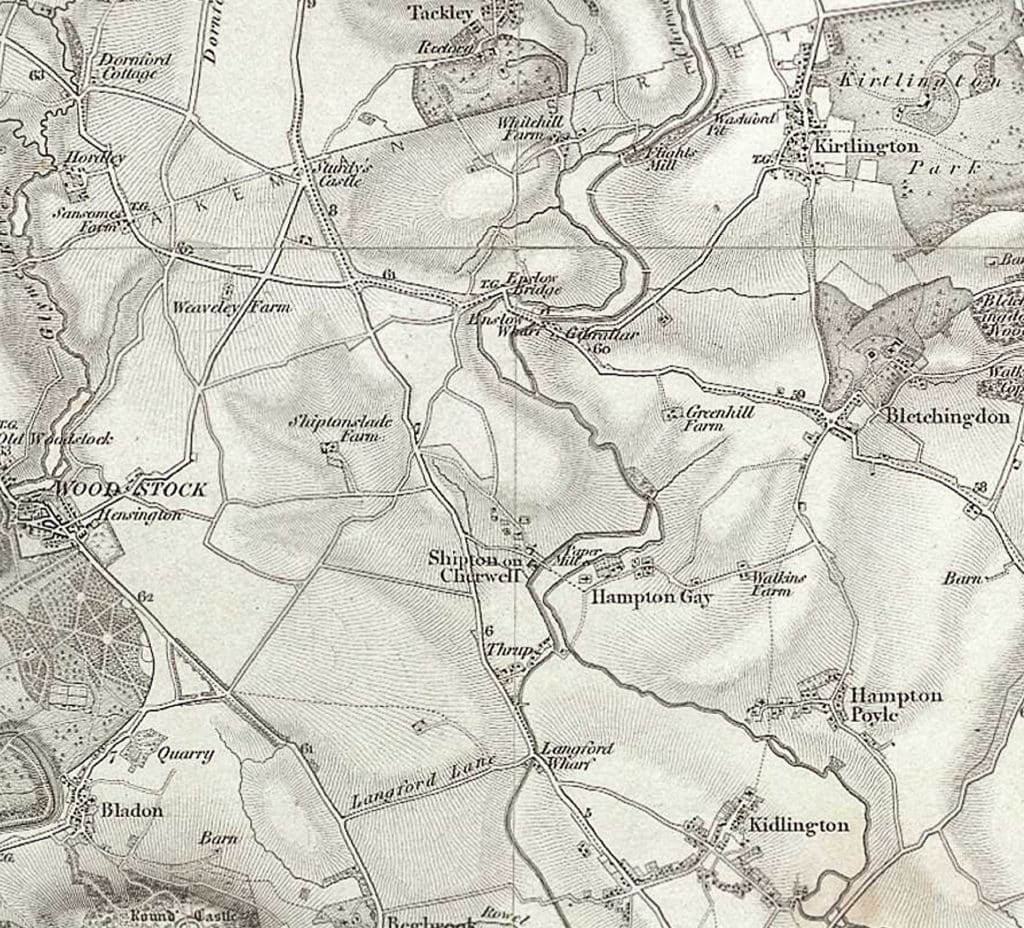

The Barry’s fortune and subsequent investment in the Manor at Hampton Gay came from John Barry, who moved to Oxford in 1536. He prospered substantially, becoming Oxford’s leading tax payer and holding the office of Alderman of Oxford, 1537-46 and Mayor 1539-41. In 1544 he purchased the Hampton Gay estate, but died just two years later, leaving some 1,900 sheep in his will.

The estate passed to his eldest son, Laurence Barry (d. 1577) and then to Laurence’s eldest son Vincent (1548?- 1615), who built the manor house. The exact date is not certain, but it probably dates from the 1580s.

Like many other landowners at the time, Vincent Barry enclosed the fields of the parish for sheep farming, which resulted in a revolt amongst the local labourers and farmers and a plot to murder him and his daughter. Barry was warned, and the revolt was thwarted. Several men were arrested and the ringleader was executed.

The Barry Inheritance

After Vincent Barry died it passed to his daughter Katherine and her husband Sir Edward Fenner (d. 1625). The next to inherit the estate was his cousin, Vincent Barry (1628-80) of Thame, Barrister-at-law and Justice of the Peace for Oxfordshire. He followed in turn by his son, also Vincent Barry (1660-1708).

The Sale of The Manor

The Rev. Vincent Barry (1660-1708), was a cleric and graduate of Oriel college, Oxford. He inherited Hampton Gay Manor from his father in 1679. In 1682, he was admitted to the Inner Temple, one of the four Inns of Court. The same year, he sold the Hampton Gay estate, sold the Manor in 1682 to Sir Richard Wenman (1657- 1690), 4th Viscount Wenman. This was possibly in order to provide for his widowed mother and other dependants. He subsequently became the vicar of Fulham. The Barry fortunes would then decline for some generations.

Re-establishment of the Barry family fortune

It was not until the nineteenth century that Sir Francis Tress Barry (1825-1907)re-established the Barry family’s fortune. He established himself in business in Bilboa and made a fortune from open cast copper mining in Portugal. Sir Francis purchased St. Leonard’s Hill, in Windsor, which he used to lend to the Prince of Wales during Royal Ascot. He was involved in various philanthropic projects, including making a Christmas gift of 6d to all the children in the London workhouses and workhouse schools. Sir Francis also owned Keiss Castle in Scotland, where he served as a Deputy Lieutenant of Caithness and financed the excavation of Nybster Broch, an Iron Age drystone structure nearby. Sir Francis had five sons and two daughters.

The following is from his obituary from the Morning Post, March 1st, 1907.

The late Baronet filled the position of British Vice-Consul for the province of Biscay, Spain, in 1846, and was Acting Consul for the provinces of Biscay, Santander, and Guipuzcoa in 1847. In 1854 Mr. Barry was offered by the Earl of Clarendon the appointment of British Consul at Madrid, but was obliged to decline it as he had established himself as a merchant at Bilbao. Returning to England shortly after, he joined his brother-in- law, Mr. James Mason, in the exploitation of the famous San Domingo copper-mines in Portugal, from which time many honours fell to him. He was decorated with the Order of Christ by the King of Portugal in 1863, five years after being raised to the rank of Commander of the same Order. In 1880 he was decorated by the King of Spain with the Cross of Naval Merit (Second Class). He acted as Consul-General in England for Ecuador in 1872. Sir Francis represented Windsor in the Conservative interest from 1890 to 1906. He was created a Baronet in 1899, and also held the Portuguese title of Baron de Barry. Sir Francis is succeeded by his son, Major Edward Arthur Barry, who was born in 1858.

The Barry Baronetcy continues to this day.

The man who returned the Manor

The story of the Barry family at Hampton Gay resumes with Stanley Leonard Barry. He was born in 1873, the fifth and youngest son of Sir Francis Tress Barry. Educated at Harrow, he became a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Berks Regiment (Militia) in 1891, and a Lieutenant in the 10th Royal Hussars, in 1894.

According to the Anglo Boer war site Barry served in South Africa in the South African War from 1899-1902 as as a Staff Captain. He was mentioned in despatches and highly decorated – receiving the Queen’s Medal with six clasps, the King’s Medal with two clasps, and the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). He also became a Brevet Major. A brevet was a military commission conferred for outstanding service but without a corresponding increase in pay.

After the South African war he served as Signalling Officer, Deputy Assistant Adjutant General (Intelligence) and Assistant Military Secretary (AMS) to General Sir John French from 1900 to 1906.

During World War One Lieutenant Colonel Barry once again served under Sir John French, now Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France. This time he served as Aide-de-Camp (ADC). He also served in attendance on HRH the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII, and the Duke of Windsor after his abdication), in the early years of the war.

From 1916 Colonel Barry served as Assistant Military Secretary, Home Forces, Horse Guards. He was mentioned in Despatches, made a Member of the Victorian Order (MVO) and a Companion of the Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (CMG) in 1915. He was also awarded the Chevalier, Legion of Honour.

After the war Colonel Barry was awarded an OBE, and was promoted to Brevet Colonel. He retired from the army in 1929 and lived in Long Crendon Manor, which was restored by renowned architect Phillip Tilden in 1920/21 under the direction of Colonel Barry’s future second wife.

Return – after 300 years

According the peerage.com, Colonel Barry married twice: Hannah Mary Hainsworth in 1906, and Laline Annette Hohler (formerly Astell) in 1927. His second wife was the widow of fellow WWI veteran and DSO holder Lt-Col. Arthur Preston Hohler, who survived the war but died soon after returning to England in 1919.

Colonel Barry had a daughter from his first marriage, Jeanne Irene Barry (1915-2008), who married the Hon. James McDonnell, the son of the 7th Earl of Antrim, in 1939.

Colonel Barry returned the Manor to the Barry family in 1928 when he purchased it from Wadham College. The family had last owned it 300 years previously, in 1628. The College had purchased it in 1862 for £17,500. It burned down just 15 years later.

The ruins of the manor remained in the Barry family after Colonel Barry died in 1943 but the story of the Barry family at Hampton Gay came to an end when his daughter, by then the Hon. Jeanne McDonnell, sold the ruins in 1975.

Photos of the Ruin

For more photos of the ruin take a look my galleries:

The cobbled Radcliffe Square containing the iconic

The cobbled Radcliffe Square containing the iconic