There is something magical to me about pictorialist photography, particularly urban pictorialism, as shown here in Leonard Misonne’s accomplished example from 1899. In addition to having the skill to take photographs with the cumbersome and slow equipment of the time, the pictorialist’s vision was realised through a complex end-to-end process that required yet more skill and talent. They had to be skilled in dark room manipulation, often made their own emulsions and embraced alternative printing methods. Some even made their own paper. So, there is much to admire about these photographers, but what exactly is pictorialism?

Summary – Pictorialism in 100 words

Pictorialism emerged in the late 19th century, driven by photographers’ desire to reinvent the medium of photography as an art form, emphasising beauty, tonality, and composition to elevate photography to the same level as painting. The Pictorialists used soft-focus, experimental techniques and processes, artisan chemicals and special papers to create their atmospheric images and increase their artistic impact. The movement was most active between 1885 and 1915. It waned with the rise of straight photography, which valued sharpness and documentary precision, but set the stage for future artistic photography and innovation in the field of photography.

But is it Art?

To explore the much asked question ‘what is pictorialism?’ we need to ask a more fundamental question that is central to the movement and its development. That is, ‘is photography art’?

From its inception, when it took a mastery of optics, chemistry, and an arcane workflow to take and process a photograph there had been a debate about the nature of photography. Was this new invention only capable of reproduction or could it transcend its machine origins and produce art?

In the early years of its development, photography was sometimes looked down upon as purely mechanical, but as early as 1853 the English miniaturist Sir William John Newton was championing the cause of photography as art. Newton also suggested that photographers could make their pictures more like works of art by throwing the subject slightly out of focus and using retouching techniques.

Influences

Hill and Adamson

Photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson had a strong influence on the development of Pictorialism. The partnership was formed in Edinburgh in July 1843, just four years after the invention of photography was announced. In the four years that followed they produced an extraordinary body of work that included portraits, landscapes and social documentary using the Calotype process.

The strong sunlight needed to produce a successful calotype meant that Hill & Adamson were required to work outdoors and one of their most important achievements was the portrayal of The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth, shot at Newhaven, a small fishing village on the outskirts of Edinburgh. The portraits are considered to be the first social documentary photographs and were compared by some critics of the time to those of Rembrandt. Alfred Stieglitz would later describe Hill as “the father of pictorial photography” and would featured the duo’s photographs in his publications and the galleries of the Photo-Secession.

Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron was also an important pictorialist influence whose pictures would be championed by Stieglitz in CameraWork (volume 41, 1913). Cameron’s photographs had a romantic and expressionist style and often used slightly blurred focus. She considered her pictures art well before the pictorialist movement got underway and took inspiration from artists such as Raphael and Michelangelo.

When Cameron received the gift of a camera in December 1863 her husband was in Ceylon attending to the family’s coffee plantations, and her children were no longer at home. Photography became her focus and a link to the writers, artists, and scientists of her well-connected circle. Although she took up photography as an amateur with no knowledge and she worked at it with great energy and once she had developed her technique started to vigorously copyright, exhibit, publish, and market her work. She developed close links to the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). IT was home to her first exhibition in 1865 and home to her portrait studio in 1868.

Cameron was an outstanding portraitist, producing brooding head and shoulders shots of the famous men of her acquaintance including English poet laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson and mathematician, scientist and photography pioneer Sir John Herschel. Her work also consisted of theatrical tableaux from myth, the Bible, Shakespeare, and the works of Coleridge and Tennyson. Today, she is considered one of the most important and innovative photographers of the 19th century.

Oscar Gustav Rejlander

Oscar Gustav Rejlander was one of the fathers of art photography, and a pioneer of photomontage. Originally a painter, he rejected the contemporary view of photography as a scientific or technical medium and made photographs that imitated painting, inspired by the Old Masters.

It was a visit to Rome in 1852 that was the catalyst for his interest in photography. Shortly after his return, Rejlander took photography lessons with Nicolaas Henneman, previously an assistant of William Henry Fox Talbot, after which he adapted his artist’s studio in Wolverhampton for photography. In 1857 Rejlander produced his masterpiece, a 31-by-16-inch image, by joining 30 negatives together. The Two Ways of Life was both technically ambitious and controversial, depicting an elaborate and moralising allegory of the choice between vice and virtue. Rejlander photographed each model and background section separately, using more than thirty negatives. These were then combined into a single large print which demonstrated the aesthetic possibilities of photography.

The picture caused a sensation initially but became the lead example in a polarised public debate on art, photography and whether combining images was acceptable.

Lady Clementia Hawarden

Rejlander admired the work of another photographic pioneer, Lady Clementina Hawarden, whose work is sometimes compared to Julia Margaret Cameron’s, though to my mind it is very different. Rejlander observed that ‘she aimed at elegant and if possible, idealised truth’.

As a Victorian woman, coming to photography in the late 1850s, Hawarden’s work was confined to her first-floor studio in her elegant Kensington home. Her images pushed the boundaries of art and photography using a careful selection of props, clothing, and model poses using her daughters as her subjects were her daughters. Their likenesses in her work were often reminiscent of the pre-Raphaelite artists.

Hawarden’s photographs demonstrated technical excellence as well as innovation and she became an expert in indoor photography. This expertise was recognised by two silver medals the Photographic Society of London.

Peach Robertson’s Pictorial Effect

Rejlander’s work also inspired Henry Peach Robinson, a British photographer who, like Rejlander, had previously trained as an artist. He achieved fame with his five-negative print of 1859, Fading Away, depicting a young consumptive dying in her bed surrounded by her family. Like Rejlander’s work, the tableau caused controversy due to the photograph’s artificial technique and morbid subject matter, with critics questioning whether a single picture from multiple negatives made photography untruthful.

Robinson, a member of the Photographic Society, published his manifesto Pictorial Effect in Photography in 1869. The work, which gave the movement its name, included compositional formulas taken from a handbook on painting and made the case that rules created for one art form could apply to another.

Emerson and Naturalistic Photography

In the 1880s the British photographer Peter Henry Emerson proposed an alternative artistic vision for photography. He was a dedicated student of the arts, influenced and inspired by the naturalist school of painters, which included Jean-François Millet. Millet’s rendered his landscapes and peasant scenes in low tones and with a softened atmosphere, but they were realistic enough for him to periodically face the charge of being a socialist.

Emerson’s vision was that photographs should reflect nature and be produced without artificial means. He believed that the tone, texture, and light of the scene were enough to make photography an art form. This point of view became known as naturalistic photography after the publication of his treatise Naturalistic Photography in 1889, in which he outlined a system of aesthetics. This treatise insisted that photography should show real people in their own environment, and avoid costumes, posed models or backdrops.

Improvements in Technology

Emerson embraced the photogravure process which was refined by Karl Klíc, a painter living in Vienna, who patented an improvement on William Henry Fox Talbot’s earlier process. The Talbot-Klíc process allowed for deeper etched shadows and the transfer of the negative image to a copper plate using gelatin-coated carbon paper. It was published in 1886.

In 1888, the introduction of the point-and-shoot Kodak camera, together with printing as a service, greatly accelerated the popularisation of photography. This only intensified the public debate about the role of the medium, which reached its peak by the end of the century.

You can read more about the development of photography in the articles From Chemistry to Computation or The Timeline of Early Photography.

As photography became popular serious amateurs, many inspired by Emerson’s ideas and images, began to explore the medium’s expressive potential. This resulted in the first truly international photographic movement – The Pictorialism Movement. The movement represented a shift of focus from Emerson’s Naturalism to the broader expression of photographers as artists.

What is Pictorialism?

The pictorialist photographers produced pictures that were the polar opposite of the output of point-and shoot. They used soft focus techniques, a range of darkroom techniques and alternative printing processes to produce beautifully rendered, skilfully composed, highly picturesque, atmospheric and often otherworldly images. These were hand printed (usually on hand-coated artist papers) using artisan emulsions and pigments, making the production of an image much closer to the creation of a painting.

The movement sometimes goes under other names including “art photography”, “Impressionist photography”, “new vision, and “subjective photography.

Pictorialism was closely linked to influential artistic movements such as Tonalism and Impressionism, and the Pictorialists took inspiration from popular art, adopting its styles and ideas to demonstrate that photography was an artistic process.

The emergence of Pictorialism was also the product of the meeting of photography and art in practical terms. Artists started to use photographs to capture images that would be rendered as paintings later, whilst some Pictorialists had been trained as painters.

No Accepted Definition

There is no accepted definition of Pictorialism. The Britannica definition is “an approach to photography that emphasizes beauty of subject matter, tonality, and composition rather than the documentation of reality.” This is helpful, though in addition to an approach it is also variously defined as a style, particularly of fine art photography, and as an aesthetic or international movement, including an art movement. The Alfred Stieglitz Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago captures much of this in this description:

“The international movement known as Pictorialism represented both a photographic aesthetic and a set of principles about photography’s role as art. Pictorialists believed that photography should be understood as a vehicle for personal expression on par with the other fine arts. Responding to both the new Kodak camera “snapshooters” and formulaic commercial photographers, the Pictorialists proudly defined themselves as true amateurs—those who pursued photography out of a love for the art.”

Understanding Pictorialism

To understand Pictorialism it’s worth reviewing what Pictorialist pictures have in common. Landscape photographer Sandy King (who still works with 19th century hand made photographic processes) offers an excellent description of its characteristics:

- Only images which show the personality of the maker, generally through hand manipulation, can be considered works of art

- An interest in the effect and patterns of natural lighting in the outdoor landscape

- An impressionistic rendering of the scene, in which overall effect is more important than detail

- The use of symbolism or allegory to reveal a message

- The use of alternative printing processes: carbon and carbro, gum bichromate, oil and bromoil, direct carbon, and platinum.

A review of the techniques Pictorialists used to convert the camera into something closer to a paint brush is also enlightening. These included dark room manipulation; the combining of multiple negatives; the use of artisan emulsions; alternative printing methods using gum bichromate and gum bromoil; the use of paint brushes and hand made paper. In addition to giving the pictures their unique look, these techniques also ensured that no two prints looked identical, even if they came from the same negative.

Who were the Pictorialists?

Some of the most notable Pictorialists are Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946); Edward Steichen (1879-1973); Edward Weston (1886-1958); Paul Strand (1890-1976); Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-79); Henry Peach Robinson (1830-1901); Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936); Robert Demachy. (1859-1936); Frederick H. Evans (1853-1943); Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882-1966) and Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934).

You can find is a more comprehensive list of Pictorialist Photographers at the A-Z of Pictorialist Photographers on this site.

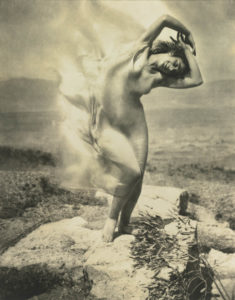

Women Pictorialists

As the A-Z list shows, many prominent Pictorialist photographers were women at a time when photography was largely male dominated. Female practitioners included Anne Brigman; Alice Boughton ; Julia Margaret Cameron; Imogen Cunningham; Mary Devens; Gertrude Käsebier; Adelaide Marquand Hanscom Leeson; Emily H. Pitchford; Sarah Choate Sears; Eva Watson-Schütze.

Pictorialist Clubs and Organisations

These photographers, who considered themselves artists, formed clubs and salons such as The Linked Ring, The Royal Photographic Society, The Photo-Club of Paris and The Trifolium of Austria all of which promoted photography as fine art. As part of the advocacy for the expressive power of the photograph these clubs and organisations produced lavish journals and exhibition catalogues featuring beautiful hand-made photogravures.

The Photo Secession

In 1902 Alfred Stieglitz formed the Photo-Secession, a society with the stated aim of seceding from the accepted idea of what constitutes a photograph. It was inspired by art movements in Europe, such as the Linked Ring. Stieglitz described the aim of Photo-Secession as “to hold together those Americans devoted to pictorial photography in their endeavour to compel its recognition, not as the handmaiden of art, but as a distinctive medium of individual expression.” He described its attitude as “one of rebellion against the insincere attitude of the unbeliever, of the Philistine, and largely of exhibition authorities”. The “membership” of the Photo-Secession was largely set by Stieglitz’s predilections. The core members were Edward Steichen, Clarence H. White, Gertrude Käsebier, Frank Eugene, F. Holland Day, and later Alvin Langdon Coburn.

The Photo-Secession actively promoted its pictorialist ideas through the influential quarterly Camera Work and the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession (also known as the 291) which provided a place for the members to exhibit their work. Painter and photographer Edward Steichen and other notable artists were instrumental in developing the program of exhibitions at the gallery, which featured exhibitions by important European artists such as Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, and the Cubist works of Pablo Picasso that would influence artists across media around the world.

By 1910 Photo-Secession had become divided over the degree of manipulation of negatives and prints that was appropriate and divided. In 1916 Käsebier, White, Coburn and others formed the Pictorial Photographers of America (PPA) to continue promotion of the pictorialism. A year later Stieglitz formally dissolved the Photo-Secession, although it had not been active for some time.

The Decline of Pictorialism

The heyday of Pictorialism was from the 1880s to 1915. Unsurprisingly for such a romantic movement it lost momentum after the World War I and was a spent force by the end of World War II. It was superseded by the sharp focus of Modernism in Europe and the West Coast or Straight photography movement in the USA, the greatest exponents of which were Edward Weston and Ansel Adams.

Later Pictorialists and Neo Pictorialism

Pictorialism had all but disappeared by the 1920s, but some photographers persisted with it. Adolf Fassbender, for example, kept making pictorial photographs into the late 1960s. In the 1990s the label neo-pictorialist was applied to some photographers influenced by the original movement. An article in Vice describes the emergence of neo-pictorialism well:

“A century after the fight for legitimacy, photography is now cycling back to its beginnings with a rise in traditional and alternative processes through companies such as the Impossible Project and Lomography seeking to reclaim analogue photography and leave behind the freneticism and immediate gratification of a digital photograph—much in the same way that Pictorialists sought to slow down the photography of their time with an eye to the myriad possibilities of the medium.”

Photography as Art

The ideas of Newton, Rejlander, Robinson, and Emerson’s were not the same, but they were all pioneers for photography to be considered a legitimate art form. This is a question that rarely crops up today, but for those who wish to ponder it I’ll take a proof point from many possible options. In 2011 a grey image of the Rhine by German artist Andreas Gursky sold for $4.3m (£2.7m) at auction, setting a new record at the time. The grey and featureless landscape was described by the artist as an allegorical picture about the meaning of life. That sounds like art to me.

More About Early Photography

If you are interested in the history of photography, you might also might these articles interesting:

- The Kodak Folding No 2 Autographic Brownie

- Autographic Photography (Kodak’s account of the benefits)

- The First Camera Lens

- Fox Talbot and Early Photography

- Wet Plate Photography

- From Chemistry to Computation (Photography timeline)

- Pictorialism

- Early Aperture Scales

- Timeline of Early Cameras

- Brassaï’s Dark and Beautiful Realm

Revision History

This article was originally written in September 2015 and was thoroughly updated and revised in March 2024.

It’s been a while…

It’s been a while…