Wet plate aka gun cotton photography

Wet plate photography was not easy. The wet-plate collodion process used between the 1850s and 1880s uses a solution of gun-cotton in ether and alcohol and requires the entire photographic process including coating the plate, exposing and developing it to be completed within fifteen minutes.

These and other challenges faced by early photographers were brought home to me by the a BBC documentary ‘Britain in Focus’, produced in partnership with the National Media Museum and presented by Eamonn McCabe. The first episode covered the earliest period of Photography in Britain – from polymath inventor Henry Fox Talbot in the 1840s to Peter Henry Emerson in the last years of the nineteenth century. The program surveyed some of the greatest pioneers of early photography in their most famous locations: Fox Talbot in Lacock Abbey, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson in Newhaven, Roger Fenton in the Crimea, Julia Margaret Cameron at Little Holland House, Robert Howlett in the Isle of Dogs and Peter Henry Emerson in the Norfolk Broads.

Roger Fenton

I was familiar with the work of most of the photographers in the program, with the exception of Roger Fenton. I was hugely impressed by his images and a little research showed him to be an extremely important photographer. Born into a wealthy banking family in 1819, he studied law at Oxford and painting in Paris before he took up photography, learning the early Calotype process developed by Fox Talbot. Fenton was a founder member of the Photographic Society (later the Royal Photographic Society), the first official photographer of the British Museum and quite possibly the world’s first officially appointed war photographer, photographing the Crimean War in the first systematic coverage of a conflict in 1855.

Wet Plate Photography in The Crimean war

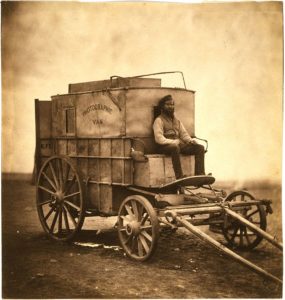

Fenton’s connections led to his commission by the British government to photograph the Crimean war – a conflict that pitted the Russian Empire against a somewhat unlikely alliance of Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire, and Sardinia. He took a photographic assistant, a servant and a large horse-drawn van converted from a merchant’s wine wagon to carry his cumbersome large format wet plate photographic equipment (see image, right). The wagon offered a good target for Turkish artillery and Fenton also suffered from the high temperatures, broken ribs and cholera. Nevertheless, and despite the long exposures and rapid processing required, he was able to capture 350 images, most of which were later exhibited across Britain and displayed to the British and French royal families.

Fenton was a technically accomplished photographer and his large format images from Crimea are striking. They consist mainly of posed portraits and scenes and landscapes of battle sites including the iconic The Valley of the Shadow of Death. Though he saw plenty of horrors during the conflict, he did not record any with his camera, most likely because his government patrons wanted the images that could be used as part of a campaign to counter reports of wide spread military incompetence in a war that was unpopular with both the press and the public.

The depth of field made possible by the large format, together with marvellous tone and composition make Roger Fenton’s work quite extraordinary. In addition to his war photography he shot royal portraits, architecture, landscapes (such as those of Bolton Abbey covered in the documentary) and still life. He regarded photography as both art and business and abandoned it entirely in 1863 to return to law when he saw its status was diminished to a craft – illustrated by the 1862 International Exhibition’s placement of photography in the section reserved for instruments and machinery. He died only a few years later in 1869.

Large format film photography

Large format film images, particularly those created using wet-plate photography, have a unique look that can not be reproduced with 35mm cameras – the shot of Roger Fenton’s wagon clearly shows this. However, the supporting image in this post is an homage to it. The shot of the ruined manor at Hampton Gay (which burned down in 1887) is a long exposure (40 second exposure at f13 using a black glass ND filter) shot in windy conditions. It is sepia toned and I added some grain and lens falloff in post production. I’ve shot the manor with a few medium format cameras (6X6 and 4.5) but at some point I’d love to shoot it with a large format, preferably glass plate, camera.