There are many strands in a photography timeline – the chemistry of film and processing, the physics of optics, the mechanical engineering of shutters, the electronics of metering and digital photography, and the iconic camera designs that bring everything together. At each end of the photography timeline, the science is bewilderingly complex – from the arcane chemical processes of early photography to the algorithms of computational photography, which enables cameras to go beyond capturing photons to compute pictures.

It’s not a linear journey; digital photography has been accompanied by a resurgence of interest in all things analogue, characterised by toy cameras, digital filters and apps that produce or replicate the look of film as well as the renewed growth of film photography. I started to shoot with film again in 2016 and around the time I first wrote this article, during the lockdowns of 2020, I started to expand my small collection of vintage film cameras and went back to film photography. There is an all-film gallery of the boats of Deal, Kent shot with a variety of film cameras including SLRs, TLRs and rangefinders here. It’s gratifying to see the growth of UK film businesses such as Analogue Wonderland, which supplies a vast range of film stock and The Intrepid Camera Company, which has reinvented large format photography for the twenty-first century. I’m as interested in looking forward as back however, and and follow new developments with great interest, including crowd funded ventures such as the AI powered Alice Camera.

I’ve reviewed, and borrowed from, many timelines and dozens of articles and books on the history of film, film processes, cameras, lenses, digital technology, phone camera development and computational photography to compile this photography timeline and in an attempt to combine these strands. The sections of the timeline are of my own devising.

I’ve tried to be diligent with my research and check the facts. The sources for the majority of entries are included as URLs. I have also referred to several excellent books: A History of Photography in 50 Cameras by Michael Pritchard; the Taschen books 20th Century Photography and A History of Photography; Photography A Concise History by Ian Jeffrey and Photography, the Definitive Visual History by Tom Ang, all of which I can recommend. If you spot any factual errors please feel free to share them with me along with the source(s).

There are two other timelines on this site, one for nineteenth century cameras and a year by year timeline for cameras from 1900. These exclude lens, photographic process and phone cameras covered in this article.

Photography Timeline 1826-2020

1826-1850 The Genesis of Photography

c. 1826 Joseph Nicéphore Niépce uses bitumen of Judea for photographs on metal and makes the first successful camera photograph, View From My Window at Gras

1827 Niépce addresses a memorandum on his invention to the Royal Society in London, but does not disclose details

1829 Unable to reduce the very long exposure times of his experiments, Niépce enters into a partnership with Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

Charles Chevalier creates a compound achromatic lens to cut down on chromatic aberration, a failure of a lens to focus all colours to the same plane, for Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s photographic experiments

1832 Robert Hunt’s Researches on Light records the first known description employing platinum to make a photographic print, but does not succeed in producing a permanent image

1835 William Henry Fox Talbot makes his first successful camera photograph or “photogenic drawing” using paper sensitised with silver chloride,

1839 The public birthday of photography, from three inventors – Dagurerre, Fox Talbot and Bayard

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s Daguerreotype becomes the first photographic process to be adopted, creating a unique image on a silvered metal plate of remarkable sharpness.

Hearing of Daguerre’s invention, Fox Talbot announces a paper process to achieve images by action of light and presents his photogenic drawings at the Royal Society in London

Hippolyte Bayard produces direct-positive images (like Daguerre’s process) on sensitized paper (like Talbot’s).

Sir John Herschel suggests fixing images in sodium thiosulphate. He also coins the terms photography, negative and positive.

The first camera to be manufactured in any quantity is the Giroux Daguerreotype, which uses a sliding box design.

Stereoscopic depth sensing is first explained by Charles Wheatstone as he invents the stereoscope

1840 The Petzval Portrait becomes the first wide-aperture portrait lens and the first photographic lens where the design was computed mathematically before construction

Alexander Wolcott opens The earliest known photography studio New York City – a “Daguerrean Parlor” for tiny portraits, using a camera with a mirror substituted for the lens

Alexander Wolcott patents a modified Daguerrotype camera using a polished concave mirror to reflect the focused light onto a photosensitive plate

The cyanotype or blue-print is invented by Sir John Herschel, the first photographic process not to use silver

Fox Talbot discovers what will be revealed as the Calotype process the following year, the first known method of multiplying an image

J.F. Goddard uses iodine to shorten exposure times for daguerreotypes

1841 Fox Talbot patents the Calotype process, or photogenic drawings that produces photographic images on salted paper – a negative-positive process that makes multiple copies possible.

The first photographic studio in Europe is opened by Richard Beard in a glasshouse on the roof of the Royal Polytechnic Institution in London

The Royal Academy of Science in Brussels displays the earliest stereographs

1843 Anna Atkins publishes the first book with photographic illustrations, using the cyanotype process.

Joseph Puchberger patents the first hand crank driven swing lens panoramic camera

1844 Fox Talbot publishes The Pencil of Nature bringing photography to the attention of a wider public

1845 The Bourquin of Paris camera is the first camera with the lens in a metal tube using a rack and pinion mechanism for focusing.

Two French Physicists, Fizeau and Foucault develop the first recognisable shutter mechanism in order to photograph the sun

1847 Louis Désiré Blanquard-Evard improves Talbot’s Calotype process and presents his research to the French Academy of Sciences

1848 Edmond Becquerel makes the first, temporary, full-colour photographs, though an exposure lasting hours or days is required and the colours sometimes fade right before the viewer’s eyes

Claude Felix Abel Niépce de Saint-Victor uses albumen on glass plates for negatives

1850 The albumen print is announced by Louis-Désiré Blanquard-Évrard, delivering greater density, contrast and sharpness than had been possible with a salted paper print.

1851-1870 Instantaneous Photography

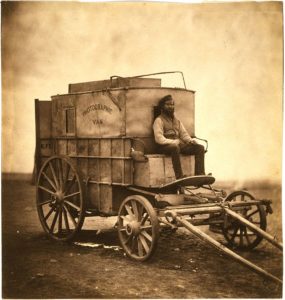

1851 English sculptor Frederick Scott Archer invents the Collodion process, or collodion wet plate process, which is 20 times faster than all previous methods and is free from patent restrictions

The Great Exhibition transforms stereoscopy from a minor scientific interest to a craze which will not wane until the 1870s

1853 The Tintype process is first described by Adolphe-Alexandre Martin – an inexpensive direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel

Thomas Ottewill registers the double sliding folding camera which combines the folding principle with the sliding box design

1854 James Ambrose Cutting takes out several patents relating to the Ambrotype process, underexposed or bleached wet collodion negatives that appeared positive when placed against a dark coating or backing

Parisian portrait photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri patents the Carte-de-visite (CdV), a new style of portrait utilizing albumen paper the size of a visiting card that will become commonly traded among friends and visitors

1855 The carbon process is patented by A. L. Poitevin, producing an image resistant to fading which becomes widely used in book illustration

1857 The folding camera with tapering bellows is invented by C.G.H. Kinnear, forming the basis for subsequent bellows designs

1858 John Waterhouse invents Waterhouse stops, a system using plates with different aperture diameters that could be inserted into a slot in the lens barrel which are the earliest selectable stops.

John Harrison Powell registers his design for a portable stereoscopic camera.

Fox Talbot perfects photoglyphic engraving, the forerunner of the they dust-grain photogravure process.

1859 Thomas Sutton introduces the Panoramic Camera, which uses a spherical water-filled lens to create a panoramic photograph

Dr. J.M. Taupenot develops the dry collodion-albumen process, though adoption of dry plate photography would come later with the gelatine dry plate process

1860 John Jabez Edwin Mayall popularises the carte-de-visite with a set of portraits of the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace published in an album

1861 James Clerk Maxwell presents a projected additive colour image, the first demonstration of colour photography by the three-colour method

The first photographic single-lens reflex camera (SLR) is invented by Thomas Sutton

Oliver Wendell Holmes creates but does not patent a handheld, more economical, stereoscopic viewer than had been available before

1862 The first successful wide-angle lens is the Harrison & Schnitzer Globe

1863 The cabinet card is first introduced by Windsor & Bridge in London, a larger form of the carte-de-visite suitable for display in parlours

1866 The Rapid Rectilinear lens is introduced by John Henry Dallmeyer, reducing distortion, coma and lateral colour

The Woodburytype process is patented, producing very high quality continuous tone monochrome prints

1868 Louis Ducos du Hauron patents the process for making subtractive colour prints on paper

The South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) offers Julia Margaret Cameron space for a portrait studio, making her the museum’s first artist-in-residence

1869 Pictorialist photographer Henry Peach Robinson publishes Pictorial Effect in Photography with a goal of teaching aesthetic concepts to photographers

1871-1900 Instantaneous Photography without the Chemistry

1871 English physician Richard Leach Maddox invents the lightweight gelatin dry plate silver bromide process, assigning the complex and arduous chemistry work photographers had previously to undertake to a factory

1873 Charles Harper Bennett improves the gelatin silver process by hardening the emulsion, making it more resistant to friction

The platinotype process, which produces platinum prints, is patented by William Willis.

1877 George Eastman learns to make his own gelatin dry plates, based on the writings of the British innovators, including Charles Harper Bennett

Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke produce Blitzlicht – the first ever widely used flash powder

1878 Heat ripening of gelatin emulsions is discovered by Charles Harper Bennett, making possible very short exposures and paving the way for the snapshot

1879 George Eastman applies for a patent for an emulsion-coating machine, which enables him to mass-produce photographic dry plates

1881 Thomas Bolas patents a hand-held, box form camera he calls a detective camera

1882 Etienne Jules Marey perfects a chronophotographic gun, a device capable of taking 12 exposures a second.

1883 Ottomar Anschütz designs a camera with an internal roller blind shutter mechanism in front of the photographic plate – the first focal-plane shutter in recognisable form

William Schmid patents the first detective camera to be widely sold

1885 The first flexible photographic roll film was sold by George Eastman, though this original “film” was actually a coating on a paper base

1886 Frederick E. Ives develops the halftone engraving process, making it possible to reproduce photographic images in the same operation as printing text

The first single use camera, the Ready Fotografer, is introduced, using a dry plate, though it appears to have enjoyed very limited success

C.P. Stirn patents the Stirn Concealed Vest Camera (or waistcoat camera in the UK) which becomes a popular and much copied design

1887 The Rev. Hannibal Goodwin files a patent application for camera film on celluloid rolls, though it will be not granted until 1898, by which time George Eastman has started production of roll-film using his own process

1888 The Kodak n°1 box camera, the first ready-loaded, easy-to-use camera is introduced with the slogan “You press the button, we do the rest.”

1889 George Eastman introduces the first transparent plastic roll film, made from highly flammable cellulose nitrate film

The Loman Reflex, the first commercially produced camera with a focal-plane shutter, is introduced

1890 The Zeiss Protar, the first successful anastigmat photographic lens, designed Dr Paul Rudolph, is introduced

Hurter and Driffield introduce the “S” shaped characteristic curve which is central to sensitometry, the science of light-sensitive materials

The Ilford Manual of Photography is first published, providing detailed technical information regarding optics, chemistry and printing.

W.W. Rouch and Co. introduce the Eureka, which will become a popular detective, or hand, camera

The German manufacturer C.P. Goerz incorporates the Anschütz focal-plane shutter into a camera

1891 Bausch and Lomb introduce the first of their iris diaphragm shutters, incorporating an f-stop and shutter speed setting device

1892 Samuel N. Turner applies for a US patent for paper-backed, daylight-loading roll film. The backing paper is printed with white exposure numbers which can read through a red window in the back of the camera. The idea is incorporated in the Boston Manufacturing Company’s ‘Bullseye” camera of the same year.

1893 The Cooke triplet lens is patented by Harold Dennis Taylor of T. Cooke & Sons, the first lens system that eliminates most of the optical distortion or aberration at the outer edge of lenses

1895 The Pocket Kodak appears, the first mass-produced snapshot camera.

Samuel Kodak recognises the potential of the Samuel N. Tuner’s daylight loading process and acquires his company, having licensed the process initially.

1896 The Zeiss Planar lens, designed by Dr Paul Rudolph, is introduced.

The Dallmeyer-Bergheim soft-focus lens produces soft definition without losing the natural structure of the object being photographed

A collapsible version of the Goerz Anschütz camera, the Ango, is introduced, which becomes popular and is widely copied

1897 Kodak markets the Folding Pocket Kodak which produces a 2 1/4″ x 3 1/4″ negative – the standard size for decades

1899 The Sanderson hand camera, the first highly flexible view camera that allows photographers to retain the correct perspective, is introduced

1900-1947 The Rise of Popular Photography

1900 Kodak bring the Brownie, an inexpensive user-reloadable point-and-shoot box camera and the most successful camera range of all time, to market

1901 The popular medium format film 120 film is launched by Eastman Kodak for its Brownie No. 2, and will become the longest surviving roll film format

1902 Carl Zeiss introduces the Tessar lens, an inexpensive design that becomes extremely popular

The Thornton-Packard Company introduces The Royal Ruby, a field camera in polished mahogany with brass fittings and leather bellows, as the King of Cameras

1903 To compensate for the curl resulting from gelatine emulsion, Kodak adds a layer of gelatine coating to the back of the film and introduces it as N.C. (Non Curl) film.

1904 Realising that tarnish reduces reflection, Dennis Taylor of Cooke Company develops a chemical method for producing lens coatings

The term Straight Photography is first used in the journal Camera Work as response to Pictorialism

The Midg No. 0, a quarterplate magazine camera that takes twelve glass plates in metal holder is introduced.

1905 The Soho Reflex large-format single-lens reflex camera is introduced and becomes the definitive SLR model until after WWII

The first telephoto lens optically corrected and fixed as a system is introduced – the f/8 Busch Bis-Telar

Thomas Manly introduces the Ozobrome process, a simplified carbon process, which becomes a favourite amongst Pictorialists

1906 Panchromatic plates, sensitive to all wavelengths of visible light, are marketed by Wratten and Wainright in England

c.1906 The Ticka, a watch-style disguised camera, is introduced and goes on to become the most popular watch-form camera ever made. It is loaded with a film carried in a one-piece drop-in cartridge.

1907 The Autochrome plate is introduced, the first commercially successful colour photography product.

1908 Kodak produces the world’s first commercially practical safety film using cellulose acetate base instead of the highly flammable cellulose nitrate base.

c. 1910 Adoption of the bromoil process begins, creating the soft images reminiscent of paint popular with the Pictorialists

1911 In Italy, The Bragaglia brothers begin experiments in photodynamism

1912 Kodak introduces the Vest Pocket Kodak, or ‘VPK’

The Graflex Speed Graphic press camera is introduced and will continue in production until 1973

1913 Kodak invents 35mm film for the early motion picture industry

Oskar Barnack, creates the Ur-Leica, the prototype of a small-format 35mm camera, doubling the width of 18x24mm cinema film and running it horizontally, rather than vertically as in cinema cameras of the time

The introduction of Eastman Portrait Film begins the transition to sheet film instead of glass plates for professional photographers

1916 The first camera with a coupled rangefinder is marketed – the 3A Kodak Autographic Special

1917 Paul Strand’s essay Photography and the New God in the final issue of Camera Works argues for images to be sharply focused and clearly camera-made

1924 The first common wide aperture lens becomes available with the f/2 Ernemann Ermanox

1923 The first fisheye lens is the Beck Hill Sky (or Cloud in the UK) lens designed for scientific cloud cover studies

1925 Leica introduces the Leica I, a watershed design that makes the 35mm format truly viable

The wide aperture Ermanox becomes available with an f/1.8 lens

1928 The Rolleiflex offers photographers superb build quality, superior optics and bright viewfinders

The Zeiss Sonnar lens is patented by Zeiss Ikon. It is notable for its relatively light weight, simple design and fast aperture.

The Vacublitz, the first true flashbulb made from aluminium foil sealed in oxygen, is produced in Germany by the Hauser Company.

1929 Minolta, originally named the Nichi-Doku (which means “Japan-German”) Photographic Company, introduces its the first camera, the Nicalette, which is equipped with a German shutter and lens.

1930 The Leica I Leica Thread Mount (LTM) offers a camera with interchangeable lenses.

LOMO (Leningrad Optical Mechanical Association) produce the first Russian-manufactured camera

c. 1931 Dr Harold Eugene “Doc” Edgerton, invents of the ‘strobe’ flash, transforming the stroboscope from an obscure laboratory instrument into a common device

Rodenstock introduces the Imagon, which will become one one of the classic professional soft-focus portrait lenses, a look strongly associated with images of Old Hollywood

Kodak introduces Verichrome film, offering greater latitude and finer grain than the Kodak NC (Non-Curling) Film that had been the standard since 1903.

1932 The Leica II is launched, the first Leica camera with a rangefinder, which becomes a signature of the company

Zeiss Ikon produce the Contax I to compete with the Leica II

Group f.64 is formed – an association of California photographers who promote sharply detailed, purist photography

The first Agfacolor film is introduced, a film-based version of their Agfa-Farbenplatte (color plate) product which is similar to Autochrome

The first photo-electric light meter is introduced, the Weston Model 617

Voigtländer introduce the Prominent, a a6x4 folding bed, coupled rangefinder camera, Voigtländer’s first rangefinder camera

1933 The Leica III is introduced and is produced in parallel with the Leica II, and will remain in production in various iterations until 1960

The first Rolleicord is introduced, a simplified version of the Standard Rolleiflex, with a cheaper 75mm Zeiss Triotar lens

1934 Kodak releases the first preloaded 35mm film, the 135 film cartridge, removing the need for photographers to load their own film into reusable cassettes in a dark room

Minolta creates the first Japanese camera to use the 6 x 4.5cm format – the Semi Minolta I.

1935 Eastman Kodak markets Kodachrome film, the first colour film that uses a subtractive color method to be successfully mass-marketed

Zeiss Ikon introduce the Super Ikonta B, a premium quality, folding medium format rangefinder camera notable both for its build and image quality

Canon introduces the Hansa, the first Asian 35MM camera.

Leica introduces the Thambar, a legendary 90mm f2.2 soft focus portrait lens

Interference-based anti-reflective coatings are invented and developed by Alexander Smakula of the Carl Zeiss optics company

1936 the first widely-distributed 35mm SLR camera, the Kine Exakta, is introduced, with a design that will influence many subsequent SLRs.

Zeus Ikon launch the Contax II, the first camera with a rangefinder and a viewfinder combined in a single window.

1937 The Rolleiflex Automat introduces automatic film loading and transport.

The Minox subminiature camera is introduced, becoming one of the most suitable cameras for covert use.

1938 Kodak Introduces the Super Six-20, the world’s first camera with built-in photoelectric exposure control

The first hot shoe appears on the Univex Mercury, though hot shoes did not become common until the 1960s.

Jaeger-LeCoultre produce the Compass Camera, an Ultra-Compact 35mm Camera, machined out of solid aluminium and designed by Noel Pemberton Billing

1939 The Argus C3 is introduced and becomes the world’s best-selling 35mm camera, offering affordable 35mm rangefinder photography to amateurs

Kodak adds a ready-mount Service for 35 mm Kodachrome Film. This makes it possible to project slides as soon as they are received from the processing laboratory.

1939-40 The Zone System is formulated by Ansel Adams and Fred Archer as ” a codification of the principles of sensitometry“, based on the studies of Hurter and Driffield

1940 Kodak introduces Tri-X film in sheet film formats

The first Minolta-made lens with the “Rokkor” name appears on a portable aerial camera used for military purposes, named in honour of Mt. Rokko.

1941 The Kodak Ektra 35mm RF is introduced with the first complete anti-reflection coated lens line for a consumer camera

1942 Eastman Kodak introduces Kodacolor – the first negative film for making colour paper prints.

1945 The Kodak dye-transfer process is introduced

1946 Kodak markets Ektachrome Transparency Sheet Film, the company’s first colour film that photographers could process themselves using newly marketed chemical kits

1948-1984: The Refinement of Film Photography and the Birth of Digital

1948 Instant photography is introduced with the first instant-film camera, the Land Camera 95 or Polaroid camera.

The iconic Hasselblad 1600F camera is introduced and goes on to develop a reputation as the ultimate professional camera.

Nikon introduces the Nikon 1 rangefinder, the first Nikon-branded camera ever produced. The design is based on the Contax rangefinder but with a simpler shutter similar to that used by Leica.

1949 The modern lens aperture markings of f-numbers in geometric sequence of f/1, 1.4, 2, 2.8, 4, 5.6, 8, 11, 16, 22, 32 etc. is standardised

The Contax S camera is introduced, the first 35 mm SLR camera with a pentaprism eye-level viewfinder

1954 The Leica M is introduced with the new Leica M mount and combined rangefinder and viewfinder

Kodak introduces high-speed Tri-X black and white film on 35mm and roll film. Aimed squarely at photojournalists, it was the first fast film for general use.

1955 The Kilfitt Makro-Kilar f/3.5 is the first macro lens to provide continuous close focusing

1957 The Asahi Pentax SLR is introduced, placing controls in locations that would become standard on 35 mm SLRs

Hasselblad introduces the medium format 500 C system camera, which will go on too become one of most influential and successful cameras of all time

1958 Minolta introduces the first achromatic lens coating – two layers of magnesium fluoride deposited in different thicknesses to radically reduce glare and flare.

1959 The Nikon F is introduced, Nikon’s first SLR and the first SLR aimed at professional photographers

The the first production varifocal (zoom) lens for still 35mm photography is produced – The Zoomar 36-82mm f/2.8 for Voigtländer Bessamatic 35mm SLRs

Kodak High Speed Ektrachrome film becomes the fastest colour film on the market

1960 Konica introduces the Konica F, featuring the Hi-Synchro, the first SLR shutter with a speed of 1/2000s

1961 Eastman Kodak introduces faster Kodachrome II color film

1962 AGFA introduces the first fully automatic camera, the Optima, with an automatic programmed exposure, using a selenium-meter-driven mechanical system

The Nikkorex F is the first production single-lens reflex camera with the metal Copal square shutter

1963 Kodak introduces the Instamatic range of cameras, with the easy-to-use Kodapak 126 film cartridge and the phrase ‘load it you’ll love it’

Polaroid launches the first instant picture colour process, Polacolor

1964 The Pentax Spotmatic SLR is introduced with revolutionary stop-down light metering

1965 The word pixel is first published by Frederic C. Billingsley of JPL

1966 The VEB Pentacon Prakica is the first SLR with an electronically controlled shutter

Zeiss produce the Planar 50mm f/0.7, the world’s fastest lens, used by NASA to photograph the dark side of the moon

The Rollei 35 is introduced as the smallest full-frame 35mm camera in the world

1967 Nikon F Photomic SLR is the first camera with a centre-weighted exposure metering system

1969 The foundations for digital photography are established with the development of the charged-couple device (CCD) at Bell Labs.

1971 Nikon introduce the F2 to succeed the legendary F with a variety of finder options.

1972 Kodak reduces the popular Instamatic Camera to pocket size with the introduction of the Pocket Istamatic Camera with the new easy-load 110 Film Cartridge, extending the cartridge loading principle to what had hitherto been known as the sub-miniature camera.

Polaroid introduces the SX-70 an improvement on previous models that ejects pictures automatically and without chemical residue,

1973 Fairchild Semiconductor launch the first commercial CCD chip (0.01 Megapixels) and the MV-100, the first commercial CCD camera.

Olympus launches the OM-1, an ultra-compact 35mm SLR that initiates the compact SLR revolution of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

1975 Steven Sasson invents the world’s first digital camera while working at Eastman Kodak which shoots shoots a mere 0.01 Megapixel image.

Bryce Bayer of Kodak develops the Bayer filter mosaic pattern for CCD color image sensors, an integral part of most digital camera’s image sensor.

Olympus launch the XA series, one of the smallest rangefinder cameras ever made, featuring a fast 35mm f2.8 F. Zuiko lens, and aperture priority metering.

1976 Canon introduces the AE-1, One of the most well known and widely circulated 35mm SLR cameras ever made

Leica experiments with the first autofocus camera system but abandons it.

The Copal Compact Square Shutter (CCS), one of the most notable focal plane shutters of the ’70s, is introduced with the Konica Autoreflex TC

1977 Fuji introduces the first zoom lens to be sold as the primary lens for an interchangeable lens camera – the Fuji Fujinon-Z 43-75mm f/3.5-4.5

The Minolta XD11 is the world’s first camera with aperture priority and shutter priority, as well as a fully metered manual mode.

Kodak enters the instant picture field with a range of cameras and a new film. Kodak instant cameras do not need a mirror to reverse the image laterally, which is a requirement for Polaroid cameras, but litigation from Polaroid soon follows.

1978 Konica introduces the C35 AF, the first point-and-shoot autofocus camera.

1979 The highly portable and collapsable medium format Plaubel Makina 67 is released

1980 The Ricoh AF Rikenon 50mm f/2, the first interchangeable autofocus SLR lens, is introduced

Nikon introduces the F3, with manual and semi-automatic exposure control.

1981 Sony introduces the Mavica, a TV camera that records TV-quality still images on magnetic floppy discs.

The Sigma 21-35mm f/3.5-4 becomes the first super-wide angle zoom lens for still cameras.

International speculation on the silver market causes a significant rise in the price of silver, an important base material for the photographic industry. Agfa-Gevaert’s struggles results in the group being acquired by Bayer.

The low-tech plastic Holga camera is introduced, which will later attain cult status with the advent of Lomography and become a major source of inspiration for Instagram.

1982 Nikon introduces the FM2, which uses an improved Copal Square Shutter to achieve an unheard-of speed range of 1 to 1/4000th second and a fast flash X-sync speed of 1/250th second.

Kodacolor VR 1000 film is announced at Photokina. It is a T-Grain film, which makes possible such a high speed film with tolerable grain.

1983 The Olympus OM-4 is the first camera with a multi-spot exposure meter, taking up to eight spot measurements and averaging them

Nikon introduces the FA, the first camera to offer a multi-segmented (or matrix or evaluative) exposure light meter, which uses two segmented silicon photodiodes to divide the field of view into five segments.

1984 LOMO begin mass-producing the LC-A, achieving popularity within the USSR and kickstarting Lomography.

The Contax T, the first in a series of high quality, exceptionally compact 35mm rangefinder cameras is introduced

Leica introduces the M6, which resembles the Leica M3 but adds a modern, off-the-shutter light meter with no moving parts and LED arrows in the viewfinder.

1985-2006: Autofocus to Camera Phones

1985 Minolta introduces the world’s first fully integrated autofocus SLR with the autofocus (AF) system built into the body – the Maxxum 7000.

1986 The disposable camera is popularised by Fujifilm with the 35mm QuickSnap, which helps to define consumer photography in the late ’80s and ’90s

The Canon T90 marks the pinnacle of manual-focus 35mm SLRs

Canon launches the RC-701 ‘Realtime camera’ the first commercially available Still Video Camera

Kodak introduces T-MAX film which is smooth, fine grained and sharp – characteristics due to its use of a tabular grain emulsion. T-MAX 100 has a very high resolution of 200 lines/mm and is often used for testing the sharpness of lenses.

1987 Canon launches the EOS (Electro-Optical System), an entirely new system designed specifically to support autofocus lenses.

Canon becomes the first camera maker to successfully commercialise Ultrasonic Motor (USM) lenses which appear with the introduction of the EF 300 mm f/2.8L USM lens

1988 The Fuji DS-1P, the first digital handheld camera, is introduced, though it does not sell

The JPEG and MPEG standards are set.

Kodak introduces the DC 210, the first “Megapixel resolution” digital camera selling for under $1000 ($899).

1989 Canon introduces the 50mm f/1.0L, the fastest AF EF mount lens, and one of the fastest lenses in the world.

1990 Adobe Photoshop 1.0 image manipulation program is introduced for Apple Macintosh computer.

Eastman Kodak announces the development of its Photo CD system

The gum oil process, a painstaking and highly expressive photographic method, is invented by Karl P. Koenig.

1991 The world’s first digital SLR is introduced, The Kodak Professional Digital Camera System (DCS) based on the Nikon F3

1992 The Lomographic Society International (LSI) is founded

Leaf Systems Inc. release the first digital camera back for medium format cameras with a 4x4cm, 4-MP CCD.

1993 The f2 35 mm autofocus Konica Hexar is introduced, one of the quietest of 35mm cameras

The instantly recognisable Nikon 35Ti compact camera is released with a distinctive analog display on top

The Canon EF 1200mm f/5.6L USM is introduced, which Canon claims as the longest focal length lens available for any interchangeable-lens autofocus SLR.

1994 The Apple Quicktake 100 is the first camera to use USB to connect to a computer.

Nikon introduces the Vibration Reduction system, the first optical-stabilized lens.

1995 The Casio QV-10 is the first camera to incorporate an LCD screen on the back for image preview and playback

1996 Eastman Kodak, FujiFilm, AgfaPhoto, and Konica introduce the Advanced Photo System (APS), enabling the camera to record information other than the image

The Canon IXUS is the first IXUS APS camera, Canon’s contribution to the launch of the APS film system and an important milestone in compact camera design

Hasselblad introduces the V-system 503 C/W medium format film camera which will continue into production until 2013

1997 Philippe Kahn publicly shares a picture via a cell phone for the first time

1998 Leica launches The M6 TTL to replace the M6 with a larger, reversed shutter dial and TTL flash capability

Kodak introduces the Portra family of daylight-balanced professional colour negative films for portrait and wedding applications.

1999 The first commercial camera phone, the Kyocera Visual Phone VP-210, is launched in Japan

The Nikon D1 is the first fully integrated digital SLR designed from the ground up, rather than a digital modification to a film SLR

2000 Sharp and J-Phone introduce the first mass market camera-phone in Japan, The J-SH04

Canon introduces the EOS D30, the company’s first digital SLR produced in-house. Previously Canon had a contract with Kodak to rebrand DCS models. It was also the first DSLR with a price tag affordable to enthusiasts.

2001 Nikon produce the manual focus FM3a, the last manual focus 35mm SLR released by a major maker

Kodak lose $60 for every digital camera according to a Harvard case study

2002 Contax launch the N Digital the first full frame digital SLR digital camera

Europe gets its first camera phone with the arrival of the Nokia 6750

Canon introduces its full-frame DSLR, the Canon EOS-1Ds

Foveon X3 sensor technology is introduced in the Sigma SD9 DSLR camera

Leica introduces the M7 with auto-exposure in aperture priority mode and an electronically controlled shutter.

2003 The film market peaks with 960 million rolls of film sold

The Minolta Dimage A1 is the first model to stabilise images by shifting the sensor instead of using a lens-based system.

2004 The Epson R-D1 is the first digital rangefinder camera

The Nikon F6 is launched. It is the sixth and last high end professional film camera since the Nikon F of 1959

2005 The Canon EOS 5D is the first consumer DSLR to feature a full frame sensor

AgfaPhoto files for bankruptcy and the production of Agfa brand consumer films ends

Kyocera announces the company is to cease production of film and digital cameras, ending one of oldest brands in photography, Contax.

2006 DALSA Semiconductor announces the worlds first sensor with a total resolution of over 100 million pixels

ISO 518:2006 specifies the standard dimensions of camera accessory shoes

Konica Minolta announces the end of camera design and production, as well as the development and production of film and photo paper

2007-Present: Smart Photography and Analogue Nostalgia

2007 Apple reinvents the phone with the iPhone, replacing the keypad with a touchscreen and adding computer-like capabilities

The Samsung B710 offers a dual lens phone

2008 Panasonic releases the Lumix G1, the world’s first mirrorless interchangeable-lens camera – which uses the main image sensor for autofocus, metering and full-time electronic viewing.

The Nikon D90 is the first DSLR with HD video recording capabilities

2009 FujiFilm launches world’s first digital 3D system

The FinePix Real 3D System includes includes the FinePix Real 3D W1 digital camera, FinePix Real 3D V1 picture viewer and 3D print capability

The Leica M9 is the first full-frame digital Leica M.

2010 Instagram, the photo and video-sharing social networking service is launched on iOS.

Apple launches the iPhone 4S and pitches it as a point-and-shoot camera killer

Worldwide demand for photographic film falls to less than a tenth of what it had been ten years before

2009 Sony introduces the first consumer back-side illuminated (BSI) sensor, the “Exmor R“, which improves low-light performance

c.2010 Photographers start to use social media filters and apps such as Hipstamatic s part of a wave of analogue nostalgia

2011 Lytro releases the first pocket-sized consumer light-field camera, capable of refocusing images after they are taken

The Fujifilm FinePix X100 is introduced, the first model in the Fujifilm X-series, a range that makes the case for the benefits of APS-C over full-frame cameras

Instagram adds hashtags to help users discover both photographs and each other

2012 Sony launches the world’s first full frame compact camera – the RX1, with a fixed 35mm F2 lens

Olympus introduces the OM-D E-M5 with a 5-axis sensor-shifting image stabilisation system – the first of its kind in a consumer camera

Nokia launches the Lumia 920, the first cell phone with an optical stabilised sensor

The Nikon D800 is introduced with the world’s highest resolution DSLR sensor

2013 Sony announces the ⍺7 which starts the full frame mirrorless revolution.

Nokia launches the Lumia 1020 phone with a 1.5 inch 41 megapixel rear sensor

Sales of digital cameras in the United States of America start to fall in terms of revenue and in unit shipments, as more consumers turn to smartphones and social media

Hasselblad discontinues the 503CW medium format film camera

2014 The HTC One M8 popularises dual lens cameras

Leica introduces the Leica T (Typ 701) with Leica’s first fully-electronic, designed-for-mirrorless lens mount

2015 Google Photos delivers AI-based organisation of images

Sony announces the first camera to employ a back-side illuminated full frame sensor, the α7R II.

Leica announces the full frame, fixed-lens compact Leica Q (Typ 116) – the first full-frame Leica to incorporate an autofocus system.

2016 Apple introduces Portrait Mode, which uses the dual backside cameras to create a depth map to isolate a foreground subject and then blur the background

Apple introduces the iPhone 7 Plus. The iPhone offers a dual camera setup with different focal lengths, 23mm and 56mm, entering the realms of telephoto on a phone.

2017 Intrepid Camera launches its Kickstarter project for a light-weight, low cost, compact 10X8 film camera.

2018 The Huawei P20 Pro provides a new triple camera system

Canon officially discontinues the EOS-1V, the company’s last remaining film camera

Nikon introduces the Z6 and Z7 mirrorless cameras.

Canon introduces the mirrorless EOS R

Google Night Sight achieves similar results to a camera on a tripod with a handheld Pixel camera phone using consecutive shots reassembled into a single image via an algorithim

Production of Ektachrome film resumes

Leica introduce the Leica M10-D, a digital camera without an LCD screen designed to combine the excitement of film with digital technology.

Researchers at Dartmouth College announce the Quanta Image Sensor (QIS) which replaces pixels with jots, where each jot can detect a single particle of light (photon)

Mirrorless cameras overtake DSLRs based on value (CIPA data)

2019 Xiaomi introduce the CC9 Pro, with five rear cameras including one with 108-megapixels

The Fujifilm GFX 100 is the world’s first medium format camera to offer in-body image stabilization, with a 102MP BSI-CMOS sensor

Nikon officially releases the 58mm f/0.95 S Noct, its fastest lens.

4.5 million digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras manufactured by CIPA companies are shipped, down from 16.2 million in 2012

2020 Samsung Introduces the Galaxy S20 Ultra with five cameras to capture 108MP photos, 100 x zoom and 40MP selfies

Nikon’s introduces the D780, its first DSLR to incorporate on-chip phase-detection autofocus, a feature inherited from its mirrorless Z series

Canon launches the EOS R series next-generation full-frame mirrorless cameras featuring Dual Pixel CMOS AF technology that provides autofocus in low-light conditions previously too dark to focus in.

The Apple 12 ships, with a new 7-element design with an ƒ/1.6 aperture for the primary camera as well as advancements to Smart HDR and Deep Fusion.

Digital camera shipments drop to a new low of 8.9 million units, down from 121 million units in 2010.

The Nikon F6 film SLR is discontinued

Mirrorless cameras overtake DSLRs based on unit volume (CIPA data)

The first large-scale image recognition system based on transformers, Vision Transformer (ViT), is introduced by Alexey Dosovitskiy and Thomas Kipf

2021 Sony introduces the ⍺1, a 50.1MP, 8.6K camera capable of shooting bursts at up to 30fps blackout-free, with 15 stops of dynamic range, real-time animal eye AF and anti-distortion shutter technology.

Olympus exits the camera market, completing the sale of its camera business to JIP, a Tokyo-based venture capital firm.

Canon ships its 150-millionth interchangeable lens for EOS cameras – an RF 70-200mm f2.8L IS USM lens

Nikon announces, and very late in the year, ships, the Z9 – the first professional camera to arrive without a mechanical shutter without rolling shutter thanks to its fast stacked shutter. It also offers the world’s fastest still image frame rate of 120 fps.

2022 OpenAI launches DALL-E 2. A portmanteau of ‘Dali’ (as in Salvador) and Pixar’s ‘WALL-E’, it offers a massive upgrade on its predecessor, with more realistic results and four-times higher resolution

Stability AI launches Stable Diffusion, a deep learning, text-to-image model based on diffusion techniques.

Midjourney, Inc. launches Midjourney, a generative artificial intelligence program and service.

Apple introduces the Photonic Engine with the iPhone 14, a computational photography technique that enhances photos taken in mid-to-low lighting conditions.

Leica introduces the M11 with a 60MP full-frame back side illuminated sensor

Japanese media organisation Nikkei reports that the compact ‘point-and-shoot’ market has retracted to 3.01m units as of 2021, a drop of 97% from its peak of 110.7m cameras in 2008.

2023 Sony launches the a9 III which delivers the world’s first full-frame global shutter sensor, which allows the camera to freeze motion in captured images with a max shutter speed of 1/80,000 second and 120 fps continuous shooting.

ChatGPT expands its capabilities by adding voice and image functionalities.

Inspiration

Inspiration Q Results

Q Results It’s been a while…

It’s been a while…

We have had colour photography since the 1930s and the invention of

We have had colour photography since the 1930s and the invention of  I have seen some astonishing black and white photography that uses very strong neutral density (ND) filters such as the

I have seen some astonishing black and white photography that uses very strong neutral density (ND) filters such as the