This article started as research into classic film cameras in movies, which led me to movies featuring photographers, and to my favourite movie Apocalypse Now, featuring Dennis Hopper as a manic photojournalist. The search for the origin of Dennis Hopper’s crazed character then took me on a voyage of discovery that proved to be nearly as winding as the Mekong River…

The Photographer of Apocalypse Now

In Apocalypse Now Dennis Hopper plays an unnamed disciple of the deranged Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who leads a renegade army of American and Montagnard troops from a remote abandoned Cambodian temple.

Hopper’s photojournalist appears at the end of Captain Willard’s (Martin Sheen) journey up the fictional Nung River to terminate Kurt’s command due to his ‘unsound methods’.

Hooper greets Willard as the ne plus ultra of combat photography; bearded and unkempt, wearing full camouflage with a red headband and sunglasses and covered in Nikon photography gear, some of it visibly battered.

Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now

Hopper’s improvisational skills and unconventional acting style shine through in his depiction of the Photojournalist. His character serves as a representation of the war’s impact on the human psyche, showcasing the blurred lines between sanity and madness in the midst of chaos. Hopper’s performance brings a sense of unpredictability and instability to the film, mirroring the disorienting nature of the war itself. Francis Ford Coppola has talked admiringly of Hopper’s dedication to his character, saying, “Dennis Hopper was out there being crazy, as usual. He was mad, but I loved him. I loved working with him.”

The Literary Inspiration for The Photojournalist

The Photojournalist appears in only three scenes, but despite these brief appearances, Hopper’s role is central to the sprawling story.

The Photojournalist is based on The Harlequin in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, a Russian sailor who was Kurtz’s only European companion for several months before the steamboat arrives, and who acted as his listener and advocate.

The Role of the Photojournalist

The Harlequin and The Photojournalist are both insiders obsessed with Kurtz’s genius who attempt to convert outsiders to his way of thinking. Here is the Photojournalist’s unsuccessful attempt to justify the severed heads on poles outside Kurtz’s headquarters:

“The heads. You’re looking at the heads. Sometimes he goes too far. But… he’s the first one to admit it.“

Both cut absurd figures: The Harlequin with his colourful patches and cheerful demeanour in such a hellish environment; the Photojournalist a parody of the crazed hippy combat photojournalist in a headband. Both have a tendency to babble.

This is the Way the World Ends

Although the Photojournalist speaks many of the The Harlequin’s lines they do not play identical roles. The Photojournalist is also illustrative of the heavy price war photographers can pay, particularly the blurred lines between observer and participant and the internal conflicts set off by the accompanying moral ambiguity. The unimaginable trauma of Kurtz’s bloody compound and all that came before it must also weigh very heavily:

“This is the way the fucking world ends! Look at this fucking shit we’re in, man!“

An Ounce of Cocaine

Coppola builds the photojournalist’s crazed dialogue around lines from the Heart of Darkness and poems by Rudyard Kipling and T. S. Eliot. These are combined with Hopper’s hippy jive talk, which may have been delivered ad lib, fuelled by Hopper’s prodigious drug intake on set.

Hopper was reputed to difficult to work with on set because he was almost always high. George Hickenlooper’s documentary about the production Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse supports this: “Dennis recounted the story to me that Francis came to him and said, ‘What can I do to help you play this role?’ Dennis said, ‘About an ounce of cocaine.’

A Pair of Ragged Claws

This is in stark contrast to Coppola’s extensive use of poetry in the Photojournalists dialogue, which comes from Kurtz reading poetry to the The Harlequin in Heart of Darkness. The exceptionally strange last line of the speech below is from T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

Captain Willard : Could we, uh… talk to Colonel Kurtz?

Photojournalist : Hey, man, you don’t talk to the Colonel. You listen to him. The man’s enlarged my mind. He’s a poet warrior in the classic sense. I mean sometimes he’ll… uh… well, you’ll say “hello” to him, right? And he’ll just walk right by you. He won’t even notice you. And suddenly he’ll grab you, and he’ll throw you in a corner, and he’ll say, “Do you know that ‘if’ is the middle word in life? If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you, if you can trust yourself when all men doubt you”… I mean I’m… no, I can’t… I’m a little man, I’m a little man, he’s… he’s a great man! I should have been a pair of ragged claws scuttling across floors of silent seas…

The photojournalist’s evident admiration of Colonel Kurtz is because he had enlarged his mind, which is also what The Harlequin admired so greatly about Kurtz in Heart of Darkness.

We Were All Crazy

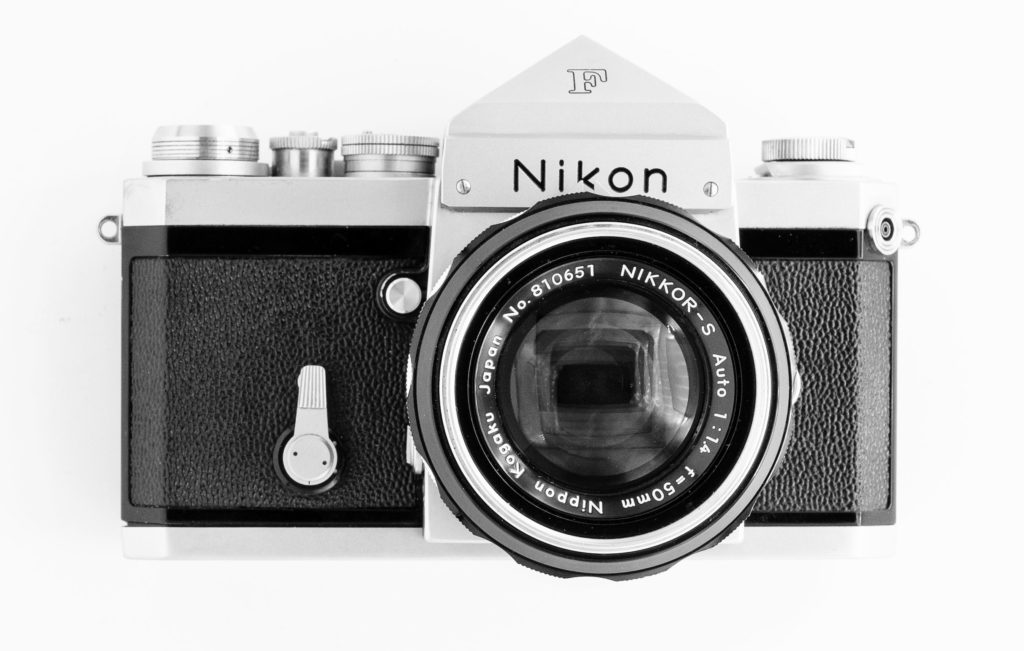

The role was suggested to Coppola by the set stills photographer Chas Gerretsen, the still photographer for film. Describing war photographers he told Coppola that “we were all crazy” – and so the role was born. Chas had served in Vietnam and routinely carried Nikon F’s, some of which he sold to the production company for use in the film.

When Dennis Hopper arrived on set Chas was asked to advise Francis Ford Coppola: “on how to dress a combat photographer” and the role of Dennis Hopper as Captain Colby was changed to the photojournalist. Chas sold three of his old Nikon F cameras with lenses to the production company and they were used by Dennis Hopper in the film. The Nikon F cameras are on display in the Coppola Winery Movie Museum.

FORGET IT

All that was left to do was to replace the role of Captain Colby, Willard’s predecessor, in which Hopper had originally been cast. Colby appears only very briefly and does not speak, surrounded by Montagnard natives and stroking a rifle. His appearance is set up in Willard’s briefing:

“There has been a new development regarding your mission which we must now communicate to you. Months ago a man was ordered on a mission which was identical to yours. We have reason to believe that he is now operating with Kurtz. Saigon was carrying him MIA for his family’s sake. They

assumed he was dead. Then they intercepted a letter he tried to send his wife :

SELL THE HOUSE

SELL THE CAR

SELL THE KIDS

FIND SOMEONE ELSE

FORGET IT

I’M NEVER COMING BACK

FORGET IT

Captain Richard Colby – he was with Kurtz.“

Bad, Dope-Smoking Cats

The Cultural References section of Sean Flynn’s entry in Wikipedia references him as the basis for the Photojournalist in Apocalypse Now. Though it is not substantiated it is entirely possible. Flynn, along with Englishman Tim Page, are portrayed as the lunatic journalists and “bad, dope-smoking cats” of Michael Herr’s classic book on the Vietnam War Dispatches.

Herr went “chopper-hopping round the war zone” with Page and Flynn, taking huge risks according to one reviewer of Dispatches. He later collaborated on the narrative of Apocalypse Now.

In Dispatches Herr described Page as the most extravagant of the “wigged-out crazies running around Vietnam”, largely due to his drug intake. Page’s Wikipedia page also describes him as part of the inspiration for the character of the Photojournalist, who specialised in wigged-out craziness:

“One through nine, no maybes, no supposes, no fractions. You can’t travel in space, you can’t go out into space, you know, without, like, you know, uh, with fractions – what are you going to land on – one-quarter, three-eighths? What are you going to do when you go from here to Venus or something? That’s dialectic physics.“

I thought dialectic physics was pure invention and part of the madness. It is not, and is helpfully described as “a living method of cognising nature and of searching for new truths in modern science, and in physics in particular” in M. E. Omelyanovsky’s Dialectics In Modern Physics.

In Like (Sean) Flynn

Whether he acted as an inspiration for the role or not Sean Flynn, the only child of hell-raising screen legend Errol, has one of the most fascinating, but also one of the saddest stories of the war.

Initially following in his fathers footsteps as an actor (his first film was Son of Captain Blood, sequel to his father’s classic Captain Blood), he abandoned the craft to start a new life in Vietnam as a combat photographer.

He exploits are truly intrepid. He shot his way out of an ambush with the Green Berets with an M16; incurred injuries from a grenade fragment in battle; made a parachute jump with an Airborne Division, and identified a mine whilst photographing troops, saving an Australian unit from potential destruction. Flynn used a Leica M2 in Vietnam, and it came to light, complete with a strap that fashioned from a parachute cord and a hand grenade pin, just a few years ago.

The Disappearance of Sean Flynn and Dana Stone

In 1970 Flynn was captured by Viet Cong guerrillas at a checkpoint along with fellow photojournalist Dana Stone. The pair had elected to travel by motorbike rather than the limos the majority of photojournalists were travelling in. Neither he or Stone were seen again. Despite the efforts of his mother to find him, Flynn was declared dead in absentia in 1984 and the fate of two remains unknown, notwithstanding the continued efforts of friends and the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), the organisation responsible for recovering the remains of fallen soldiers.

Sean Finn’s story is told in a film inspired by his life entitled The Road to Freedom which was filmed on location in Cambodia in 2011. It also the subject of an eponymous track on the album Combat Rock by The Clash.

A CIA Kurtz?

Whilst the role of Colonel Kurtz and his ‘unsound methods’ was clearly inspired by ‘Heart of Darkness’, there is another potential influence which is less well known. This is revealed in the UK documentary ‘The Search for Kurtz’ which describes how CIA Paramilitary Operations Officer Tony Poe and his leadership of Operation Momentum, which was launched in 1962 to turn the Laotian Hmong people into anti-communist guerrillas.

The Wrath of Klaus Kinski

Another significant influence for the Vietnam river epic is Aguirre, Wrath of God by Werner Herzog, starring a barely sane Klaus Kinski in the role of his life. The story follows the self styled ‘Wrath of God, Prince of Freedom, King of Tierra Firme’ Lope de Aguirre, who leads a group of conquistadores down the Amazon River in search of El Dorado, city of Gold.

It is an astonishing and spectacular film, described by Robert Egbert as is “one of the great haunting visions of the cinema”. Curiously, I did not make the connection with Apocalypse Now until researching this article. Like Apocalypse Now, which was troubled by a heart attack, an overweight star, a mental breakdown and storms that destroyed the sets, the filming of Aguirre is the stuff of legend. Herzog allegedly pulled a gun on Kinski to force him to continue to act in the remote fever-ridden jungle district where the film was shot.

Has a character in a movie, especially an unnamed one, ever had such a rich set of sources?

The Photojournalist’s Cameras

The Photojournalist’s cameras are Nikon Fs with a variety of lenses; possibly a fast 50mm, a 105mm and a 200mm. This isn’t a a surprising photographer’s rig as the Nikon F, along with the Leica M2, was the leading film camera of the Vietnam war and carrying multiple cameras was common. Richard Crowe a former Combat Cameraman who served between 1966–1972 described the practice on the Q&A website Quora:

“If we are talking about photojournalists, they usually carried two to three 35mm cameras each with a different focal length lens. Nikon and Leica cameras were the favorites and the photojournalists usually owned their own equipment. The guys that I worked with often carried both a Leica with a UWA lens and two Nikons with normal and short telephoto lenses. The Canon SLR cameras of the day would often not stand up to the rough usage and dirt and grime in Vietnam. The photojournalists began to paint the silver portions of the camera bodies black so the camera would not be a point of aim for a sniper. Later on, camera companies began to supply cameras with black bodies and called them “Photojournalist Models”. BTW: no photojournalist that I knew or met ever carried a zoom lens on his camera. The early zoom lenses for SLR cameras were pretty crappy in image quality.”

Notable Vietnam War Nikon F users included Eddie Adams, Larry Burrows, Tim Page, Henri Huet, Dana Stone, Philip Jones Griffiths and Don McCullin, whose F famously stopped a bullet from an AK47.

The Legacy of the Nikon F

The Nikon F was not the first SLR, that distinction belongs to the Exakta, which is the subject of another blog about photographers – Rear Window. Prior to its introduction, however, no SLR could challenge the mighty German rangefinder in the 35mm camera market; SLRs were often compared unfavourably to rangefinders as heavy, slow and less than reliable, with dim viewfinders.

The F swept away that dominance and many professional photographers abandoned Leica for Nikon. Leica lost its market dominance and never recovered it, though it has prospered in its niche of late.

The Nikon F brought many advancements to market simultaneously:

- A system camera with interchangeable viewfinders and focusing screens

- An automatic diaphragm and an instant-return mirror, which made it the quickest SLR by far.

- An impressive lens line up

- A large reflex mirror that kept the viewfinder bright, and reduced vignetting

- A 100% viewfinder, an SLR first

- A focal plane shutter with titanium-foil blinds—also a first

These advancements made the technical advantages of the SLR over the rangefinder compelling. The need to match lenses to frame lines and for external viewfinders to use wide angle lenses disappeared. Gone too were the framing and parallax compensation issues and the limitation on zoom and lenses longer than 135mm.

Over time the F became legendary for indestructible levels of reliability and durability. It still casts a long shadow.

The Legacy of Apocalypse Now

Apocalypse Now is an iconic movie, savage and darkly comic, and an expedition through insanity from start to finish. It is widely considered one of the greatest films ever made. I have watched it many times and it has retained its power for me.

Robert Egbert said of it: “Apocalypse Now is the best Vietnam film, one of the greatest of all films, because it pushes beyond the others, into the dark places of the soul. It is not about war so much as about how war reveals truths we would be happy never to discover.“

Related Articles on Flash of Darkness

If you enjoyed this article, another movie that is a favourite of mine and features a photographer is Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window. The journey wasn’t quite as twisting as Apocalypse now but it was interesting nonetheless…

There are also two articles on classic film cameras in the movies on this site – one of Leica and one on Nikon.