For a camera maker of such influence, Thomas Ottewill is biographically elusive. We have examples of his cameras, but we know little about his business, less about his family life and nothing at all about his final years and death. In this article I have attempted to assemble what is known and research what is not.

Much remains unknown, but what follows is a timeline of his life and cameras, based on the many sources that can be found online, followed by a summary of his legacy. The main source for the cameras is the excellent British Camera Makers, an A-Z Guide to Companies and Products.

Context: Photography 1851-1865

Thomas Ottewill was a leading figure in the shift from opticians and instrument-makers to a specialised manufacturing and retail industry, with British firms scaling up the production of cameras, lenses and sensitised materials. During that period, much else changed.

It is the collodion era. Frederick Scott Archer’s wet collodion (1851) rapidly displaces the daguerreotype and calotype because its glass negatives offer an improvement over the calotype process, which relies on paper negatives, and the daguerreotype, which produces a one-of-a-kind positive image. By the International Exhibition of 1862 the catalogue could state that, “with some few exceptions, all [exhibits] were produced by the collodion process.”

Albumen paper, developed by Blanquart-Évrard in 1850, becomes the dominant print, pairing with collodion negatives and enabling large-scale production.

The period witnesses mass adoption via new formats: the carte-de-visite (patented in 1854) turns portraiture into an affordable, collectible commodity and stereoscopy becomes a household entertainment after its 1851 Crystal Palace showing.

Photography professionalises and institutionalises. The Photographic Society (RPS) is founded in 1853 with the explicit mission to promote the art and science of the medium, publishing the Journal of the Photographic Society from the same year.

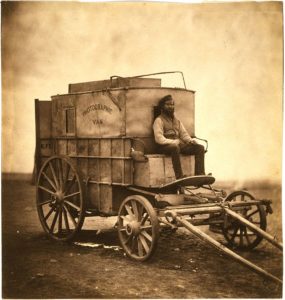

It also expands in purpose, illustrated by Roger Fenton’s 1855 Crimean War campaign, one of the earliest systematic documentary projects of conflict.

These are Thomas Ottewill’s times. This introductory description of the period is necessarily brief, so for more context you might like to read the Early Photography Timeline on this site or perhaps the articles on Made with Collodion, Fox Talbot, The First Camera Lens, and Wet Plate Photography.

Formative Years

1821 Thomas Ottewill is born in Maidstone, Kent, a town where many nineteenth-century Ottewills originated from, moving to London for work as the century progressed. The surname itself is a rare southern variant of Ottewell/Ottiwell/Otwell from the Norman personal name Otuel. (Sources: 1861 Census, Government Records Office, Geneanet.com)

1842 Thomas marries Jane Dyson, daughter of Robert, Coachman, at St. Pancreas in May. Thomas is working as a Cabinet maker and living at Clark’s Place Islington. (Source: marriage record)

1844 Thomas and Jane’s first child, Henry is born. The couple went on to have four sons and three daughters, as shown in 1861 census. Sarah Jane, 1846; Alfred, 1848; Amelia, 1851; Herbert 1853; James 1856; Emily 1858. (Source: 1861 Census)

Early Career

Pre 1851 Ottewill works at London optical and photographic firm Horne, Thornthwaite & Wood (‘Horne & Co.’) prior to starting his own firm. (Sources: Early Photography, Advertisement 16th July in Notes & Queries)

1851 Ottewill launches a business at 24 Charlotte Terrace, Islington, initially specialising in daguerreotype apparatus, as Thomas Ottewill. (Source: Company Details, Early Photography)

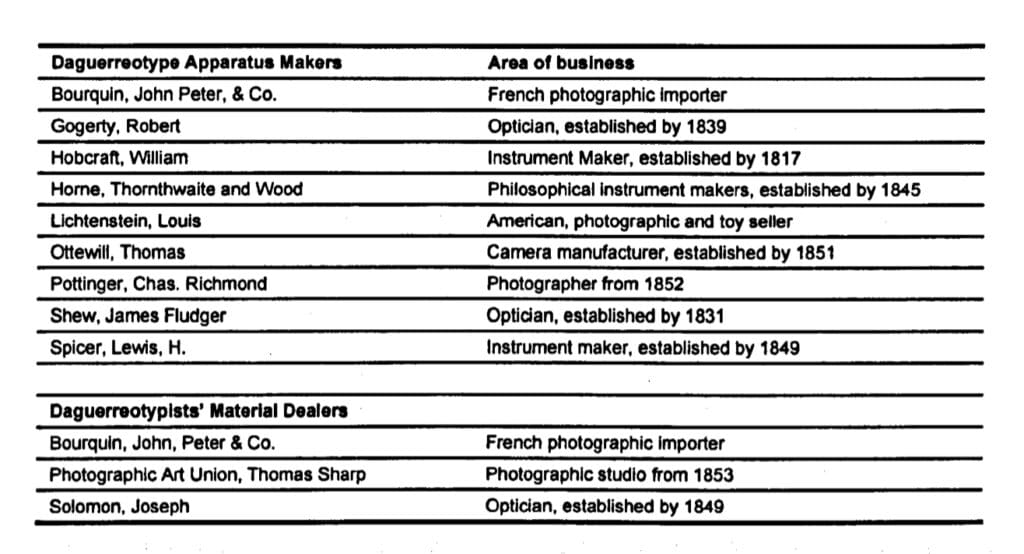

As can be seen in this listing, Ottewill was both early and unusual as a specialist camera-maker in 1851. The table above shows that most London suppliers in the daguerreotype era came out of optics (e.g., Shew, Gogerty) or “philosophical/instrument” shops (Horne, Thornthwaite & Wood; Hobcraft), with only “Thomas Ottewill, camera manufacturer” listed as a dedicated maker.

This listing was made only a dozen years or so after photography’s 1839 debut, and in the same year collodion breaks through, which puts Ottewill in the first-wave of camera makers, and distinct from the opticians who typically focused on lenses and retail and often jobbed out wooden bodies.

Over the 1850s–60s the trade would diverge. Opticians like Ross concentrated on lenses/branding while specialist cabinet-shops (Ottewill, later Hare, Meagher and Garland) built the cameras. These were frequently rebadged for the opticians and other retailers. Ottewill sits right at that pivotal point: he trained hands from cabinet-making, sold under his own name, and also manufactured for optics houses, helping move camera production from the bench of the general “instrument maker” into dedicated camera workshops.

Cameras

Thomas Ottewill started by producing Dagurrotype cameras. Whilst his first cameras are likely to have been sliding box cameras, his first identifiable camera model is the folding sliding-box of 1853.

1853 OTTEWILL’S DOUBLE FOLDING CAMERA (1853): sliding box (registered design), for 10 × 8 inch wet-plates. Once the lens panel and focusing screen frame had been removed the inner and outer boxes folded inwards on side hinges. (Lewis Carroll, the author, is said to have been a user of one of the Double Folding models). (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn)

This wet-plate camera featured a collapsible design, where the front and back panels could be detached and placed flat on the baseboard to create a compact, field-portable package. The design is described in detail on the Early Photography site:

Ottewill’s design combined the folding principle with the sliding box design. Both the inner and outer boxes carry hinges on their sides so that they can fold inwards and collapse. The outer box folds from a little way above the baseboard, this leaves space for the folded inner box. To collapse the camera remove the dark slide, remove the front panel, open the door on the top of the outer box, with the inner box drawn back a frame can now be seen at the front of the inner box, this is removed, both boxes will now collapse.

Ottewill advertises the camera in Notes and Queries in June that year: T. OTTEWILL (from Horne & Co.’s) begs most respectfully to call the attention of Gentlemen, Tourists, and Photographers, to the superiority of his newly registered DOUBLE-BODIED FOLDING CAMERAS, possessing the efficiency and ready adjustment of the Sliding Camera, with the portability and convenience of the Folding Ditto. Every description of Apparatus to order.

The reaction to the camera at the time was effusive. Photographic Journal (then Journal of the Photographic Society, December 21, 1853) praised its combination of strength and portability writing “there is none which more fully combines the requisite strength and firmness with a high degree of portability and efficiency.”

The Role of the Simple Sliding Box Camera

Whilst Ottewill’s folding double-body was aimed at field work where bulk and weight mattered, a good deal of photographic work, such as portrait studios and copying, prized body rigidity and alignment over compactness. A plain sliding-box has fewer joints, less flex, and is therefore potentially more rigid, which was important when mounting the heavy lenses of the time.

Partnerships Form and Dissolve

1854 The business becomes a partnership: Ottewill & Morgan, with William Morgan, about whom nothing else seems to be known.

1855 The partnership of Ottewill & Morgan is dissolved on the 12th April. The business rebrands to Thomas Ottewill & Co, a partnership between Thomas Ottewill and photographer/artist Frederick Aaron Gush (1817-1869). Gush was the brother of Victorian portrait painter William Gush (1813-1888).

Bellows and Stereoscopic Cameras

1856 CAPTAIN FOWKE’S CAMERA: one of the first to use bellows: the front (fixed), and rear (moving) standards secured to a baseboard. The front standard carried a tapered wooden, four-sided extension to hold the lens panel. This model was still being advertised, with improvements, in 1858, and shown as available in teakwood

Captain Fowke’s Camera was one the first camera with concertina-pattern pleated bellows, designed by Capt. Francis Fowke, R.E., patented No. 1295 (31 May 1856). Ottewill built the production examples.

Ottewill’s advert for Fowke’s Portable/Bellows Camera described it as “Invented for and used by the Royal Engineers… the most portable as well as the lightest camera in use.” (Source: National Science & Media Museum blog)

By 1856 Ottewill claimed to ‘have erected extensive workshops adjoining their former shops, and having now the largest manufactory in England for the making of cameras, they are enabled to execute with dispatch any orders they may be favoured with’ (source: Advertisement, Photographic Notes, no. 14,vol. 1, 1November 1856, p. 229.)

Ottewill continues to advertise in Notes and Queries: OTTEWILL’S REGISTERED DOUBLE-BODY FOLDING CAMERA, with Rack-work Adjustment, is superior to every other form of Camera, and is adapted for Landscapes and Portraita, – May be had of A. ROSS, Featherstone Buildings, Holborn and at the Photographic Institution, Bond Street.

1857 SINGLE LENS STEREOSCOPIC CAMERA: required two pictures to be taken in succession; the camera being slid along a slightly curved track on a mounting platform to make the two exposures. (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn)

Charles Dodgson immortalises Ottewill’s double-folding camera in a parody of Longfellow’s poem ‘Hiawatha’, in which he describes the camera, the wet-collodion process and the process of making a photograph.

Architect-photographer C. G. H. Kinnear’s designs a tapered-bellows field camera. The introduction of bellows was a milestone in camera design as it provided a lightweight method of extending body sections. Kinnear’s tapered bellows enabled the camera to fold into a very compact form because each pleat nested into the next, larger pleat. Ottewill and other manufacturers would later make improved versions of the camera.

Ottewill & Co. expands operations, occupying adjacent properties and “extensive workshops.” The company claimed to be the largest camera maker in England at the time.

1858 STEREOSCOPIC BOX CAMERA: a folding/collapsible box; much the same as the designs of Meagher and Hare. In 1859 advertised as the NEW STEREOSCOPIC BOX CAMERA. (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn)

A ‘Monster camera’, an oversized, large-plate version of Captain Francis Fowke’s folding bellows camera built by Ottewill, is shown at the 1858 Photographic Society exhibition. I can’t locate its dimensions, but period price lists show Ottewill selling very large formats (≥24×22 up to 30×30 inches), which is likely the class to which the 1858 “monster camera” belonged. For example, C. E. Clifford’s illustrated catalogue (National Art Library/RPS copy; ca. 1860–63) lists the sizes of “Improved Double-Body Folding Camera” in a table, which runs to 30×30 inches.

On the 18 May 1858 The Ottewill Gush partnership dissolves by mutual consent. Ottewill assumes all debts and continues the business alone; Gush moves on to other partnerships.

An Early Swing Back

1859 IMPROVED KINNEAR’S CAMERA: conventional design; optionally with swing back. The sizes in which this model was made have not been traced specifically but they are known to have been made in a range, or to special order. (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn – they suggest 1860s for the introduction)

The “Improved Kinnear Camera”, was derived from the design of architect-photographer C. G. H. Kinnear’s tapered-bellows field camera of 1857. A Christie’s lot essay says Ottewill made an Improved Kinnear-pattern camera in 1859 and “claimed [it] was the first to introduce a swing back.”

A swing back is an adjustable rear standard: the ground-glass/plate frame pivots on one (or sometimes two) axes so the sensitized plate needn’t stay square to the baseboard. The swing back was used chiefly for plane-of-focus control and small compositional refinements.

Whilst Ottewill’s swing back was undoubtedly early, some sources state that the movement was introduced earlier:

Tilt and Swing to the Back. These movements are found on studio cameras as early as the 1840s. Cameras fitted with tilt and swing are shown in Knight’s catalogue (1853) and described in Willats’s catalogues of 1849 and later. The 1849 catalogue claims it was introduced by Dr Leeson in 1845. (Source: Early Photography)

Meagher shows a Kinnear-derivative with a swing back described at a Photographic Society meeting in 1860.

Regardless of who introduced it first, by the mid-1860s the movement is routine on studio cameras, becoming a standard control on professional models through the 1870s.

The Early 1860s, Growth and Bankruptcy

1860 OTTEWILL’S MINIATURE CAMERA mahogany, with a brass lens mount and very similar in appearance (apart from the material) to the Skaife Pistolgraph… even to the wooden box and ball-mounted stand. Simple flap-type shutter (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn)

1860s OTTEWILL’S DOUBLE-BODY FOLDING CAMERAS; and the SUPERIOR SLIDING-BODY FOLDING CAMERAS: made in a range of (unspecified) sizes — the latter in vertical/horizontal format, or in a square pattern; optionally in mahogany or teak (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn)

This 1860s “double-body” and “superior sliding-body” models are an evolution of the 1853 model offering more formats (vertical/horizontal/square), materials (including teak), and working features like repeating backs, while staying within the sliding-box-folding tradition that distinguished Ottewill’s field cameras.

1860s STUDIO CAMERAS and PORTRAIT CAMERAS: several types and sizes of sliding-box cameras; some with sliding/repeating backs (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn)

1861 The census of that year shows Ottewill employs 21 men and 3 boys. On the 31 December Ottewill files for bankruptcy. The court requires Ottweill to surrender himself to Henry Philip Roche, esq, a Registrar of the said Court, at the first meeting of creditors, on the 15th of January the following year. (Source: London Gazette)

1862 On the 15th of March, the Bankrupty Court grants Ottewill an Order of Discharge. (Source: London Gazette)

The Collis Partnership and Debtors Prison

1863 The firm evolves into Ottewill & Collis & Co., with James Collis (formerly with Ross & Co.) as partner. Ross was a leading London firm of “manufacturing optician.” that had introduced an influential doublet portrait lens in 1841, placing the firm among the earliest English manufacturers of photographic lenses. Ottewill made much of the connection. An 1867 advertisement stated that they had been manufacturing for Ross for 15 years and that Mr Collis was previously working for Ross for 13 years.

1864 In October Ottewill is adjusged bankrupt for a second time, and is held as a Prisoner for Debt in the custody of the Sheriff of Middlesex, at No. 1, Breams’-buildings, Chancery-lane. (Source: London Gazette).

The Breams’ buildings were not a prison like Newgate , but a Sheriff’s officer’s “sponging-house” (lock-up) used to hold debtors after arrest on a writ while they tried to settle or arrange terms. A debtor was seized by a sheriff’s officer and taken to a sponging-house, and only if no arrangement was made would he be brought before the court and committed to prison.

Contemporary descriptions of Chancery-Lane lock-ups paint a picture of closely supervised rooms, fees for everything, and constant pressure to pay. Debtors could receive visitors and have food sent in, but at their own expense, while officers’ charges mounted. (Sources: The National Archives and The Spectator Archives)

Last Mention

1865 Ottewill faces creditor hearings and examination. The last mention of him appears late in that year in the London Gazette relating to his bankruptcy material.

1867 James Collis, a former employee of Ross in the accounts department, is accused by Ross of embezzlement and £20 is offered for his apprehension. (Source: Early Photography).

Late 1860s: OTTEWILL’S PLATE CHANGER: one of the earliest designs; carried eighteen plates and could be used on any suitable camera taking a conventional plate carrier. (Source: British Camera Makers, Channing & Dunn – no date for introduction provided)

43 Barbara Street Islington

A note that Ottewill was “possibly living at 43 Barbara St., Islington” in 1870 from the Early Photography site, is the last mention I can find of Thomas Ottewill.

The 1871 census shows Jane Ottewill living in 43 Barbara Street, working as a dressmaker with her daughter Sarah (also working as a dressmaker), James (aged 15, working as a stationer) and Emily (aged 12, scholar). Jane is listed as married, not as a widow.

After domestic service, needlework (dressmaking, millinery, shirt-making) was the default resort for urban women, mostly piece work done at home, often working extremely long hours in poor conditions. Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor records peak-season extremes with women “working frequently their 20 hours a day… often sitting up all night”. These were the conditions later reformers would call the “sweating system.”

Given Thomas’s first bankruptcy was a decade earlier (31 Dec 1861), and that his financial troubles continued on-and-off from then on, It is likely that Jane to begin taking in paid work well before the 1871 census records it. Michael Pritchard’s The development and growth of British photographic manufacturing and retailing 1839-1914 notes that “the business stopped completely for a period of months” when Thomas Ottewill was made bankrupt in 1864, which would necessitate anohter income to feed the family.

It is quite likely that Jane’s work shifted from supplemental to principal income as Thomas’s finances collapsed the second time.

I have not been able to find any records to confirm Thomas’s death. Jane appears to have died in 1889 in Islington (Oct-Dec 1b/173) aged 70.

Legacy

At the 1862 International Exhibition the work of ‘the photographic cabinet-makers’ George Hare, Patrick Meagher and Thomas OttewiIl drew much attention. One reviewer, Samuel Highley, noted that their cameras ‘are of the very best of English workmanship, and contrast very favourably with the productions of our foreign neighbours’. All three businesses were specialist camera makers with photographic manufacturing being the major part of their businesses. (Source The development and growth of British photographic manufacturing and retailing 1839-1914, Michael Pritchard)

Looking back, the British Journal Photographic Almanac in 1898 noted that Ottewill ‘may be regarded as the source to which the best school of English camera-making traces its origin’

From these reviews we can conclude that both as a maker and mentor, Thomas Ottewill helped set the course of early British camera manufacture. His workshop trained a small group who went on to lead the trade, including George Hare, Patrick Meagher and John Garland, T. Mason and A. Routledge so that his influence propagated through their later firms.

In design terms, he showed innovation with the double-folding field camera and Captain Francis Fowke’s bellows camera marked a key transition from sliding boxes to bellows. By the mid-1860s his workshop helped popularise Kinnear’s tapered-bellows idea with “Improved Kinnear” models, while continuing to supply leading optics houses. His equipment was praised by Charles Dodson (Lewis Carroll) and reached royal hands. The Royal Archives preserve bills from Ottewill & Morgan and Ottewill & Co.

Ottewill’s legacy is one of refined, durable cameras that helped define British field and studio work, and a training pipeline that seeded excellence across the London trade.